“Is it worth learning quantitative skills?” I remember asking a pair of action researchers some years ago. “They’re useful insofar as they give tools for understanding social processes,” they said.

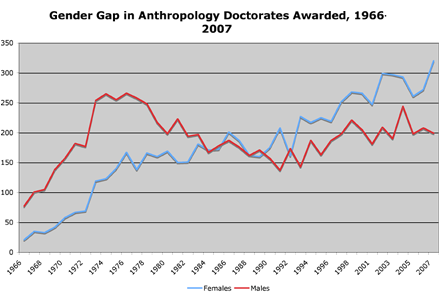

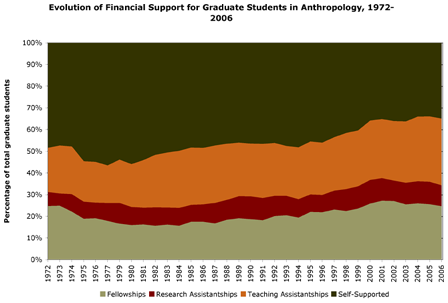

But I didn’t follow up on that at all until I recently started reading the “socio-demographic” work of Charles Soulié, a Bourdieuian French sociologist of universities whose research interests are fairly close to mine. The premise of this research is something like this: by examining the comparative history of enrollments and teaching jobs across disciplines, one can examine what Soulié calls the “evolution of the morphology” of academic fields. This isn’t very hard-core quantitative research by statisticians’ standards, I note — he doesn’t exhibit tedious anxieties about the uncertainties in his sources, nor does he propose mathematical models or major statistical analysis of his data. The methodology seems to be, in essence, visual inspection of the evolving demographics of disciplinary enrollments. He takes these as indicators of things like the “relative position of sociology in the space of disciplines,” and comes up with findings that are like:

- Sociology produced half as many graduates in philosophy in 1973, but now things are reversed, and in 2004 sociology produced 2.6 as many graduates as philosophy. This is an indicator, for Soulié, of sociology’s rising comparative importance in the university system (and philosophy’s stability, which in context was a relative decline).

- In 1998/99, “the fraction of children of professionals and upper management rose to 28.4% in letters and human sciences, against 23.1% in sociology and 38.1% in philosophy” — which tells us something important about the comparative class basis of sociology vs. philosophy at that point in time [updated to clarify: these examples refer to French academia].

I find this kind of thing quite interesting and revealing – hence this series of posts on the demographics of my own discipline – but I wonder about its epistemological basis. What does it mean, actually, that one discipline has more students enrolled than another? Is it right to speak of a competition between disciplines for students? What makes one discipline more “attractive” or “desirable” than another at a given moment? It’s not like students pick their courses based on a completely rational response to a job market, or even an idea market. In fact, it’s not clear that “market” is a good description for these kinds of systems; as Marc Bousquet has often argued, talk about the academic “job market” (for instance) disguises the fact that university administrators actually dictate the academic job system, by deciding to opt for hiring adjuncts, grad students, etc. Likewise, shifts in degrees issued, in enrollments, etc, may not necessarily be the result of “competition” or market forces (whatever one’s stance on the empirical existence of said market forces). There can be other kinds of systematic processes at work; the “morphology” of the disciplines as revealed in their enrollments doesn’t tell you everything about processes of interdisciplinary conflict and coexistence.

But the brute fact remains that there have been major historical shifts in how many students anthropologists educate, and major shifts in how large our discipline is vis-a-vis other disciplines. And these aren’t just arbitrary. They need to be explained, if we’re to understand where our discipline actually exists in the world. When American anthropology is educating a small fraction of a percent of college students, that’s not something that just happens by chance.

I feel here the strong sense of a bias in my own discipline against quantitative analysis. It’s somewhat jarring, from the narrow confines of an anthropologist’s culturalist background, to look at these comparative figures. In cultural anthropology, I think there is a widely shared consensus view today that goes something like this: culture is inherently qualitative, folded over on itself in swathes and patches and wrinkles of rich, dense symbolic significance; it would necessarily be deformed, or at best severely limited, by any effort to reduce it to a general and/or quantitative analysis. Among cultural anthropologists, numbers and quantitative facts are apt to be taken not as means of analysis, but as objects of cultural analysis and symbolic forms in their own right. So we get studies of the cultural effects of perniciously quantifying, rationalizing, neoliberal projects; and we see arguments about how the obsession with the quantitative is itself merely another local cultural phenomenon, and not a privileged, master form of knowing about the world. Often these kinds of arguments are made casually, in passing, or are simply taken for granted, inscribed in our disciplinary habits.

Continue reading “Disciplinary socio-demography, and anthropological prejudice against quantification” →