Christine Musselin, a French sociologist of higher education, ventures an interesting interpretation of the changing relation between professional status, salary, and the overall size of the academic profession. In short, she argues that the larger academia gets, the lower status professors will have.

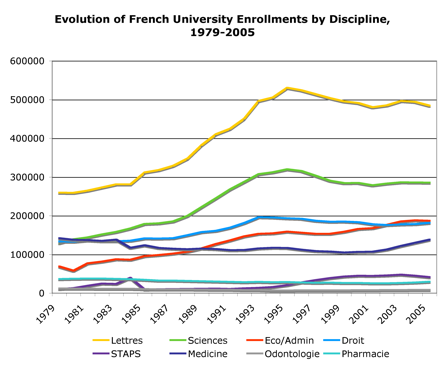

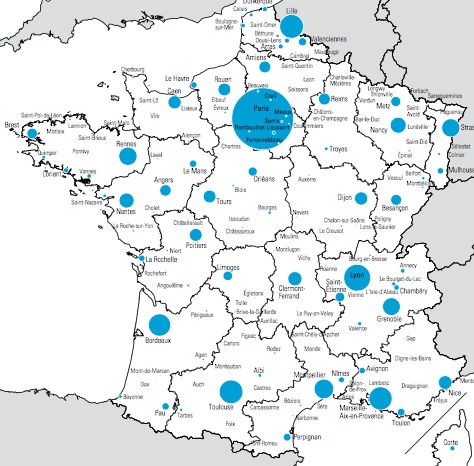

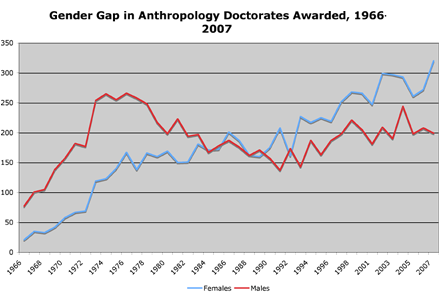

The massification of higher education has not only had demographic implications. It has led to a certain trivialization of university faculty’s social position in developed countries — it is no longer rare to be an academic. At the same time, it is no longer rare to be a university graduate. This trend should increase in the years to come, in spite of the stagnation of demographic growth in developed countries as enrollments among 18- to 25-year-olds, by cohort [classe d’âge], tend to plateau or even decline. But official policies in most developed countries, as we enter the third millennium, nonetheless aim to increase access to higher education. In France, the objective of the post-2007 government, like that of its predecessor, is to bring 50% of each age class to bachelor’s [license] level. The idea is to facilitate underprivileged or underrepresented populations’ access to education, to encourage the pursuit of studies through graduation, to encourage further studies and teaching all throughout the life course. One should not thus expect a decrease in the population of university teachers in the years to come; one should expect growth, aimed at accommodating students with more and more diversified profiles in terms of age, sociological composition, motivation, etc.

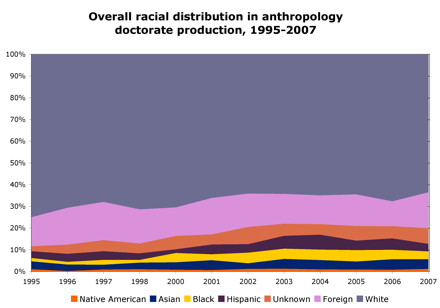

These developments are often described as one of the signs of contemporary societies’ transition towards “knowledge societies” [sociétés de connaissance] one of whose notable characteristics is a break with the concentration of knowledges [savoirs] within a handful of heads. University faculty, as they become more numerous and come to play a central role in this process, will be less and less able to maintain the quasi-monopoly of knowledge [connaissance] expertise that they have held in the past.

The progressive loss of social prestige should thus continue — at least for the larger part of the professoriate, who won’t be in the avant-garde of scientific production, but will rather primarily contribute to the transmission of knowledge and the training of highly qualified personnel. This evolution has already been in progress for a long time and can be measured in particular by looking at salaries. University faculty salaries have evolved less favorably than those of professionals with the same level of education working outside academia (for France, see Bouzidi, Jaaidane and Gary-Bobo [2007]). This trend goes for most of the university models concerned [here in this study], whether quasi-completely public as in Europe or partly private as in North America, whether the academics are state functionaries or have private-sector contracts.

(Musselin, Les universitaires, 2006, pp. 25-26, my translation.)

My sense is that academics’ “status loss” is somewhat more complex than this, since, if you believe what you read on academic blogs, most American college students can’t tell the difference between an adjunct with really low institutional status and salary and a tenured professor. So on the level of everyday phenomenology of professional life, Musselin’s description seems a little hasty. But there is certainly a sort of myth, at the very least, that (American) faculty used to get more respect than they do now; and it may well be the case that students, on the whole, demonstrate less exaggerated obsequiousness than they once did. And it’s hard not to agree with Musselin that this shift likely is deeply related to the massification of higher education: as if the more people go to college, the less prestige they gain from it – and the less prestige their teachers garner from teaching them. As if there was a kind of prestige mimesis, such that the lower status of today’s less elite student populations was contagious. Some longer meditations on the relation between prestige and scarcity may be in order here: Graeber’s, for example…