I’ve been re-reading Butler’s work lately because I’m thinking about political mimesis, and I was struck along the way by her very frank and admirable comments about the fact that if you write a bunch of things over time, you don’t necessarily want to go back over them to make sure that your view is the same everywhere.

Category: philosophy

What students say education is for

Sometime earlier this spring I asked the students in my Digital Cultures class to each write down a sentence (on a post-it) about what education was for.

Michel Foucault’s attitude towards women

One could write numerous things about masculine domination in French philosophy, and many have done so. Right now, for instance, I’m engrossed in Michèle Le Doeuff’s programmatic 1977 essay on this question, “Cheveux longs, idées courtes (les femmes et la philosophie),” which appeared in Le Doctrinal de Sapience (n° 3) and was translated in Radical Philosophy 17 (pdf).

Plato and the birth of ambivalence

I’ve been teaching a class on anthropology of education this fall, and we spent the first several weeks of class reading various moments in educational theory and philosophy (Rousseau, Wollstonecraft, Dewey, Nyerere, Freire). The first week, we read Book 2 of Plato’s Republic, which (famously) explains how the need for an educated “guardian class” emerges from the ideal division of labor in a city. Our class discussion focused mostly on Plato’s remarkably static and immobile division of labor, a point which rightfully seems to get a lot of attention from modern commentators on the Republic. (Dewey put it pretty succinctly: Plato “had no perception of the uniqueness of individuals.”)

But I was more intrigued by Plato’s remarkable, zany account of the origins of ambivalence, which I don’t think has gotten so much recognition. We have to be a bit anachronistic to read “ambivalence” into this text, to be sure, since the term in its modern psychological sense was coined by Eugen Bleuler in 1911. Nevertheless, I want to explore here how Plato comes up with something that really seems like a concept of ambivalence avant la lettre. It emerges in the text from his long meditation on the nature of a guardian, which is premised on the initial assumption that the guardian’s nature (or anyone’s nature) has to be singular and coherent.

Derrida on complacency and vulgarity

In Benoît Peeters’ biography of Jacques Derrida, there is an intriguing interview with Derrida that was never published. Peeters writes:

In 1992, Jacques Derrida gave Osvaldo Muñoz an interview which concluded with a traditional ‘Proust questionnaire’. If this text, meant for the daily El País, was in the end not published, this is perhaps because Derrida deemed it a bit too revealing:

What are the depths of misery for you?: To lose my memory.

Where would you like to live?: In a place to which I can always return, in other words from which I can leave.

For what fault do you have the most indulgence?: Keeping a secret which one should not keep.

Favourite hero in a novel: Bartleby.

Your favourite heroines in real life?: I’m keeping that a secret.

Your favourite quality in a man?: To be able to confess that he is afraid.

Your favourite quality in a woman?: Thought.

Your favourite virtue?: Faithfulness.

Your favourite occupation: Listening.

Who would you like to have been?: Another who would remember me a bit.

My main character trait?: A certain lack of seriousness.

My dream of happiness?: To continue dreaming.

What would be my greatest misfortune?: Dying after the people I love.

What I would like to be: A poet.

What I hate more than anything?: Complacency and vulgarity.

The reform I most admire: Everything to do with the difference between the sexes.

The natural gift I would like to have: Musical genius.

How I would like to die: Taken completely by surprise.

My motto: Prefer to say yes.

[From Derrida: A Biography, p. 418]

One could say many things about this. But for now, I mainly want to observe that I am struck by the open sexism of admiring “thought” as a woman’s virtue while singling out “vulnerability” (in essence) as his preferred “quality in a man.” Of course, one of Peeters’ interviewees remarks that “In spite of his love of women and his closeness to feminism, he still had a bit of a misogynistic side, like many men of his generation.”

He doesn’t hold back his criticism

I was looking at one of my interviews with philosophy professors and was struck by this little explanation of why he had not picked someone as his dissertation supervisor (directeur in French):

– Normalement j’aurais dû faire ma thèse avec XYZ, car c’était lui qui m’avait le plus inspiré, mais je connaissais suffisamment XYZ pour savoir que je ne réussirais jamais à faire une thèse avec XYZ.

– C’est-à-dire ?

– C’est-à-dire que c’est quelqu’un dont la moindre remarque m’aurait blessé au profond, et comme c’est quelqu’un qui ne menage pas ses critiques, je pense que, euh, j’aurais pas pu, quoi. Bon, je vais pas raconter ça, parce que c’est un peu intime, mais c’était pas possible, quoi. Voilà.

In English, here’s how that comes out:

“Normally I should have done my thesis with XYZ, because he was the person who had inspired me the most. But I knew him well enough to be sure that I would never manage to do a thesis with him.”

“Meaning?”

“Meaning that he’s someone whose tiniest comment would have hurt me so deeply, and as he’s someone who doesn’t hold back his criticism, I think that, uh, I couldn’t do it. Well, I’m not going to tell you about that, because it’s sort of personal. But it wasn’t possible, eh? Voilà.”

The cruelty of criticism can shape an academic career, we see. Personal acquaintance with academics can trigger revulsion. And pure intellectual commonality (“inspiration”) is no guarantee of human solidarity.

That’s what I learn from this little moment. That, and the sheer sense of blockage that can set in when academics stop to retell their lives. You’re reminded of moments of impossibility, of those structural dead ends that are as much subjective as institutional. “It wasn’t possible, eh?” he summed up. As if that was the whole story (even though he also told me he wasn’t going to tell me the whole story).

(On a more positive note, this interview does remind me of one piece of practical advice. If you are interviewing in French, and are otherwise at a loss for words, c’est-à-dire? — “meaning?” — is almost always a good way to get people to keep talking.)

Revisiting field interviews

I’ve been going back lately to my interviews with French philosophy teachers and students. I just never had time to transcribe or work on most of them during my dissertation, so I have a backlog of dozens of taped interviews, most of which are quite long and rich. I’d like to transcribe all of them, since I’m under less pressure to finish a manuscript right now, and I think they may have some documentary value in their own right.

It’s a strange, intense experience to relive conversations that took place five, six or seven years ago. All the anxieties of fieldwork come back to me; I’m annoyed by my own vague, poorly structured questions, and by the imperfections in my French accent. Often I’m amazed by the richness of my interlocutors’ experience, and their impressive ability to recount things to me, in spite of my limits as an interviewer.

One thing that becomes inescapably clear from these interviews is that the structure of a narrative is a shared accomplishment. I was quite entertained today by a moment where my interviewer took more responsibility for narrative continuity than I did:

Philosophers without infrastructure, Part 2

Following up on my last post (and indirectly on a couple of older posts), I came across an interesting interview extract that comments in a bit more detail on the lived experience of being a philosopher with practically no work infrastructure. Here’s a philosopher from Paris 8 commenting on his workspace:

Professor: “I don’t think I’m giving you any scoop in saying that, on the material level, the Philosophy Department is the poorest one in the country. It’s clear — it’s very clear, even. When, for instance, young colleagues were arriving after I got here — at the moment I’m thinking of Renée Duval who sent me a message asking, so, where was her office [Laughter] although she didn’t have an office. And, you know, even at Paris 7, if you want to meet, I don’t know, Frédéric Gauthier, I say Frédéric Gauthier because we know each other pretty well, so, indeed, he will make an appointment with you in his office.”

A department secretary interrupts: “Still, they don’t have their own offices, they have a shared office for teachers.”

Professor: “Non non non non non non non. Gauthier, he has an office, and there are other offices. At most, they’re two to an office. Of course! No, here, it’s on the edge.”

Secretary: “Yes, it’s on the edge.”

Professor: “Yes, here, it’s borderline scandalous. Meaning that, for example, we wouldn’t have to be meeting here [in the staff office space].”

Secretary: “Mais non, I agree with you.”

Professor: “Mais oui. And, well, there’ll be an office, we would be in the office, indeed, we could both of us shut the door. So for example, the master’s thesis exams happen here [in the staff office space].”

Me: “Really, they’re here?”

Professor: “Yes, it happens — and so people who show up, we can’t prevent them, it’s the office — where they turn in their homework, where they come for information, but, still, it’s scandalous. The first year, when I came, throughout practically the whole first year, I spent the first twenty minutes of class with the students looking for a room. It’s since been stabilized, but—“

Continue reading “Philosophers without infrastructure, Part 2”

Philosophical lab infrastructure

The short version of this post: Philosophers have practically no lab infrastructure.

The long version:

Coming back to my research about philosophy departments in France, I was recently reading an institutional document describing the (highly-rated) research laboratory for philosophers at the University of Paris-8. Apparently it was a bureaucratic requirement to write a section describing the “infrastructures” available to the laboratory. But since Paris-8 is a typically underfunded public university, operating in cramped quarters on a small campus in the Parisian banlieue, the sad reality is that their infrastructure was quite limited. To the point of comedy.

I quote:

Infrastructures

L’unité dispose d’une salle de 35 m2, équipée d’un téléphone, de deux ordinateurs fixes et d’une connexion par WIFI. Elle est meublée de tables, chaises, et bibliothèques. Elle est située dans un bâtiment neuf de moins de deux ans. La surface disponible par chercheur membre de l’équipe à titre principal est de 1,5 m2.

The unit possesses a room of 35 m2, equipped with a telephone, two desktop computers and WiFi access. It is furnished with tables, chairs and bookshelves. It is situated in a new building less than two years old. The available surface per principle laboratory researcher is 1.5 m2.

One and a half square meters per researcher is just about enough to cram a chair into, and clearly not enough for any sort of individual workspace. Accordingly, there were none; the room in question was purely used to hold small seminars. The whole laboratory staff would never have fit inside it, and when they did have meetings, they took place elsewhere.

There is, of course, something charming about the plaintive note that at least the tiny room is “situated in a new building less than two years old” (the building pictured above). It’s as if the author felt obliged to put only the most positive spin on a clearly inadequate situation. Nevertheless, there is something to learn here about what counts as infrastructure for philosophers at Parisian public universities: in short, all the productive infrastructure (the books, the libraries, the computers, the desks) is elsewhere, generally at home, and the campus becomes purely a place of knowledge exchange, not of knowledge production. Which is why it it is possible to have a philosophy lab with practically no facilities.

On real problems

I came across a confrontational moment in one of my interview transcripts. We had been talking about philosophers’ metanarratives about “truth.” But my interlocutor found my questions a bit too oblique.

Philosopher: But I don’t know — you aren’t interested in the solutions to problems?

Ethnographer: The solutions to philosophical problems for example?

Philosopher: Problems! Real ones! For example do you consider that the word “being” has several senses? Or not? Fundamental ontological question. Do you accept that there are several senses or one? It changes everything. And what are your arguments one way or the other?

Ethnographer: Well me personally I’m not an expert—

Modernity isn’t philosophical

Here’s a tidbit from before Sarkozy was President that gives a certain sense of how his administration was likely to regard philosophy, and the humanities in general:

« Nicolas n’est pas quelqu’un qui se complaît dans l’intellect, assure le préfet Claude Guéant, directeur de cabinet place Beauvau, puis à Bercy. J’ai beaucoup côtoyé Jean-Pierre Chevènement. Il lisait de la philosophie jusqu’à 2 heures du matin, c’était toute sa vie, les idées prenant parfois le pas sur l’action. Nicolas, lui, est d’abord un homme d’action. Quand il bavarde avec Lance Armstrong ou avec un jeune de banlieue, il a vraiment le sentiment d’en tirer quelque chose. Dès qu’il monte en voiture, la radio se met en marche. Il aime les choses simples, les variétés, la télévision. En cela, il exprime une certaine modernité. Les Français ne passent pas leur temps à lire de la philosophie… »

“Nicolas isn’t someone who revels in the intellect,” asserted the prefect Claude Guéant, chief of staff at the Ministry of the Interior and then at the Ministry of Finance. “I’ve spent a lot of time with [the Socialist politician] Jean-Pierre Chevènement. He read philosophy until two in the morning, all his life, ideas sometimes took precedence over action. Nicolas, on the other hand, is primarily a man of action. When he chats with Lance Armstrong or with a kid from the slums, he really feels like he’s getting something out of it. As soon as he gets in a car, the radio’s on. He loves simple things, variety, TV. In that, he expresses a certain modernity. The French don’t spend their time reading philosophy…”

A certain modernity is the opposite of time wasted on philosophy books…

Philosophizing in senior year?

I met an interesting professor in Aix earlier this spring, Joëlle Zask, who has worked on Dewey and early 20th century culture theory (she suggested the Sapir article I mentioned earlier this spring). Here I want to translate a short interview she did in 2007 with a monthly culture magazine in Marseille called Zibeline. Philosophy, as foreign readers may or may not know, is taught to all French high school (lycée) seniors, has a long political history in French education, and periodically causes controversy. Some of these stakes are apparent here.

Philosophizing in senior year???

1) The 2003 “official instructions” for the philosophy teaching program in senior year say: “Philosophy teaching in senior year… contributes to forming autonomous minds, warned of reality’s complexities and capable of putting to work a critical consciousness of the contemporary world.” What do you think of this?

These formulations pose two major problems.

First, it strikes me as shocking that a philosophy textbook should begin with a series of “official instructions.” An instruction, in the sense of a directive, is entirely contrary to the “autonomous minds” that we are told to “form.” Are we told to “force our students to be free”? Moreover, in the context of schools, “instruction” has a second dimension: we still talk about “public, obligatory, civic instruction” [in connection with public education]. But instructing is not educating. Instructing basically means shaping someone’s mind to fit the competences that the institution judges socially useful. Educating on the other hand means communicating a potential to a mind which, one day, will allow it to help define what is or isn’t valuable for its society. Yet according to the “official” declarations, we’re still on the model of instructing, in both senses of the term.

Second, the goal proclaimed for high school philosophy teaching is completely exorbitant. I know that many people subscribe to it. But we should be astonished by the excessive disproportion between the end and the means: they have groups of thirty pupils, a very limited range of practical exercises, lecture courses, etc. And above all, it’s impossible for philosophy teachers to “form autonomous and critical minds” if the pupils haven’t been invited to be autonomous or critical since the day they arrived in the schoolhouse. Not to mention that the art of thinking isn’t reserved for philosophy. Would one be exempted from “thinking for oneself” in history, literature or physics? It must be said that the goal [of our philosophy teaching] is, in our present circumstances, pretty disconnected from these realities; and we might therefore give up on grading students’ homework against an ideal that very few people can claim to have attained. We could, at least for starters, propose simpler exercises that would be better adapted to our students’ competences (the ones “formed” by our instruction) and to our own. At the university we do all this readily enough.

2) What should be at stake in philosophy teaching? What should be its goals?

Well, I don’t want to say that there’s nothing special to expect from philosophy teaching. To my eyes, philosophy is in essence a critique of our values and an effort to demonstrate, by one method or another, the legitimacy or pertinence of the values we hold. The philosophers who we’ve read and reread over the centuries have all undertaken an examination of the values of their times. That said, these philosophers don’t play the moral purity card [la carte de bonne conscience]. They direct their critical examination at themselves, working with their own keen perceptions of the possibilities and blockages of their epoch. Today, as in the past, many people, including our official instructors, defend some values without examination and try to impose them on others. Wondering where our values come from, going over them with a fine-toothed comb and sorting them out, creating new ones, scrutinizing the motives for our adherence to them and the mechanisms that inculcate them — that’s what a reading of the philosophers can invite us to do. And that’s a truly priceless service.

Like Zask, I’ve been struck by the official rhetoric in France about teaching people to have free and critical minds, which always seems to entail, as Zask points out, the contradictory project of “making” people free, and to presuppose the unlikely premise that educational institutions know what freedom or criticality are. But I’m most interested, here, in the part of the interview that proposes a definition of what’s essential about philosophy: a critique of values.

Philosophy classroom art

In the Philosophy Department at Paris-8, the biggest philosophy classroom is located just beside the department offices. It has a variety of curious things on its walls.

A painted character hangs from a coat rack. He appears striped. Bald. Stretched out by the neck. Striped shoulderbag too.

My friend Emmanuel proposes that we translate this as, “At Paris VIII in the philosophy department, I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by LMD.” Alternatively, “had our minds blown by LMD”… the Law LMD being one of the first university reforms of the last decade (2003). I’m not sure who’s represented by this skeletal face: the government? the philosophers? But I note the little hint of Greek architecture in the broken columns: classical Greece often seems to be iconic of philosophy in France (more, I think, than in philosophical circles I’ve come across in the U.S.).

Haiti and the poetry of broken utopias

And what does it mean when a research project that thought it was about France and about arcane educational questions suddenly finds itself confronted with an event from across the sea? What does it mean when the question of the intellectual production of a single academic department in the Parisian banlieue turns out to be in part about how the university becomes a site for the reception and mediation of mass trauma?

Part of the answer involves this poem I came across today, by Jean Herold Paul, a Haitian doctoral student in philosophy at Paris-8 (a department that turns out to have long-standing links with Port-au-Prince). I’ve translated it with his permission for you all.

The night that we are

(in memory of Jésula and Wilmichel)

bric-a-brac of apocalypses

bric-a-break of our utopias

and if…

and then…

but are we still?

in the night where we are

in the night that we are

a horrible night

where only our dead appear dimly

without name or register

without farewell or burial

in the night where we are

in the night that we are

what’s left of us?

bric-a-brac of apocalypses

bric-a-break of our utopias

in the night where we are

in the night that we are

it’s still night

at least our presence is reflected there

a simple sensation of being somewhere

without knowing who we are

where we are

without knowing with what or with who we are

in the night where we are

in the night that we are

when will we be able to mourn

for ourselves?

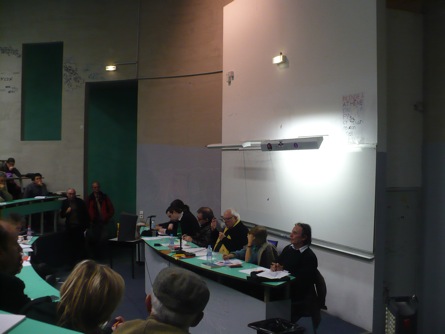

Decommunized communist colloquium

A couple of weeks ago, there was a big conference on communism at Paris-8. I went to an afternoon session that had Etienne Balibar and Alex Callinicos, curious to hear what kind of intellectual project could be made out of communism in these post-Soviet, often antisocialist, and post-20th-century days. The conference took place in a big, decrepit lecture hall in Bâtiment B. It looked like this:

A raised table, poorly lit by a fluorescent lamp shining on the whiteboard and a dim incandescent light aimed high on the wall & accomplishing nothing. Two microphones, passed back and forth between panelists. Debris of paper and waterbottles. Notebooks. Five men, one woman. Semi-formal dress: coats and jackets, Balibar in a vast yellow scarf, collars peeking out from unbuttoned shirts. Some are leaning back, the two to the left seem to be maybe whispering to each other, a couple take notes, the man at right stares out into space hands clasped as if the audience weren’t even there. (We will come back to this point.)

The future of the “knowledge society”: Philosophy and university politics in contemporary France

There’s so much that I want to write about that somehow I end up not writing anything. So as a bit of a placeholder, let me post a current draft of my diss. research proposal (taken from the NSF research proposal). It’s a bit long for a blog post, I warn you, and is still very much under revision. More new material soon, I promise.

1. Introduction: Clashing futures in university politics

What is the future of French universities in a globalized world? According to the Magna Charta Universitatum, signed by a number of rectors of European universities in 1988, “the future of humankind depends largely on cultural, scientific and technical development; and this is built up in centers of culture, knowledge and research as represented by true universities” (Rectors 2003:6). But not everyone in Europe shares this utopian view of universities as the salvation of the human species. In the midst of French protests against university reforms in 2007, the Department of Philosophy at the University of Paris-VIII held a meeting to discuss the campus strikes. According to the minutes: “Questions were raised about concerns over finding work. That one would worry about one’s future – to say the least – doesn’t mean that one wants one’s concerns instrumentalized by and for projects that will make the future even darker still” (Paris8philo 2007). In other words, in the thick of the political fray, these philosophers viewed academic knowledge not as the future of humankind, but rather as an uncertain defense against a world of scarce employment and darkening futures.

On french sociology of philosophy

I’ve been reading a lot of French sociology of philosophy, and it continues to frustrate me that the major American text in this genre, Randall Collins’ The sociology of philosophies (1998), basically makes no reference to this literature. Admittedly, the French subfield I’ve examined is relatively limited in scope, basically amounting to a very elaborate exploration of the French philosophical field, which is construed in generally orthodox Bourdieuian terms. There’s a lot of stuff about publishing markets, access to jobs, different forms of symbolic capital. But as far as I can tell, the whole French enterprise is dramatically more empirically involved than Collins’ over-ambitious project to theorize all of philosophy throughout world history. (Mostly this involves drawing little network diagrams of who knew whom.)

Continue reading “On french sociology of philosophy”

increased American interest in philosophy

An article called “In a New Generation of College Students, Many Opt for the Life Examined,” in the Times, reports that the number of undergraduate philosophy majors is climbing across the country. The interesting thing is that the reasons given for the increase in enrollment are far from traditional justifications for philosophical inquiry. A student at Rutgers, Didi Onejame, is said to think that philosophy “has armed her with the skills to be successful.” What are these skills? “It’s a major that helps them become quick learners and gives them strong skills in writing, analysis and critical thinking,” says the executive director of the APA. Students also, apparently, find it “intellectually rewarding,” “a lot of fun,” good training for asking “larger societal questions,” and a good choice for an era when the job market changes too fast, supposedly, to pick a more reliably marketable field.

Continue reading “increased American interest in philosophy”

Philosophy course listings, University of Vincennes 1969/70

According to a curious book, Christopher Driver’s The Exploding University – a journalist’s reflective late-60s tour of universities around the globe – the courses offered at the University of Vincennes as of 1969/70 were as follows:

- La 3ème étape du marxisme-leninisme: le maoïsme (Judith Miller)

- Problèmes concernant l’idéologie I (Judith Miller)

- Problèmes concernant l’idéologie II (Jacques Rancière)

- Théorie de la 2ème étape du marxisme léninisme: le concept du stalinisme (Jacques Rancière)

- Introduction aux marxistes du XXème siècle: (1) Lenine, Trotsky, et le courant bolchévique (Henri Weber)

- (2) Les écrits de Mao Tsé Toung (Henri Weber)

- La dialectique marxiste (Alain Badiou)

- La science dans la lutte des classes (Alain Badiou)

- Problèmes de la pratique révolutionnaire (Jeannette Colombel)

- L’idéologie pédagogique (René Scherrer)

- Logique (Houria Sinaceur)

- Epistémologie des sciences exactes et des mathématiques (Houria Sinaceur)

- Epistémologies des sciences de la vie (Michel Foucault)

- Pb. épistemologiques des sciences historiques (François Chatelet)

- Critique de la pensée spéculative grecque (François Chatelet)

- Nietzsche (histoire et genéalogie) (Michel Foucault)

- Les idéologies morales d’aujourd’hui (Françoise Regnault)

- A propos de la littérature et del’art (François Regnault)

- Le signe chez Nietzsche (François Rey)

Continue reading “Philosophy course listings, University of Vincennes 1969/70”