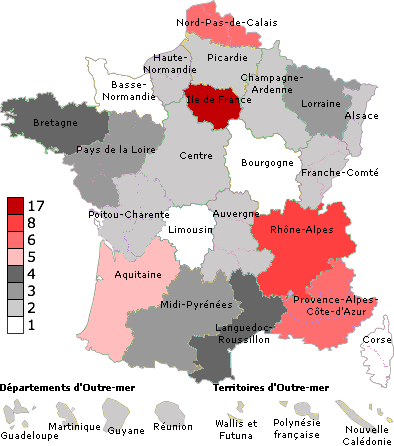

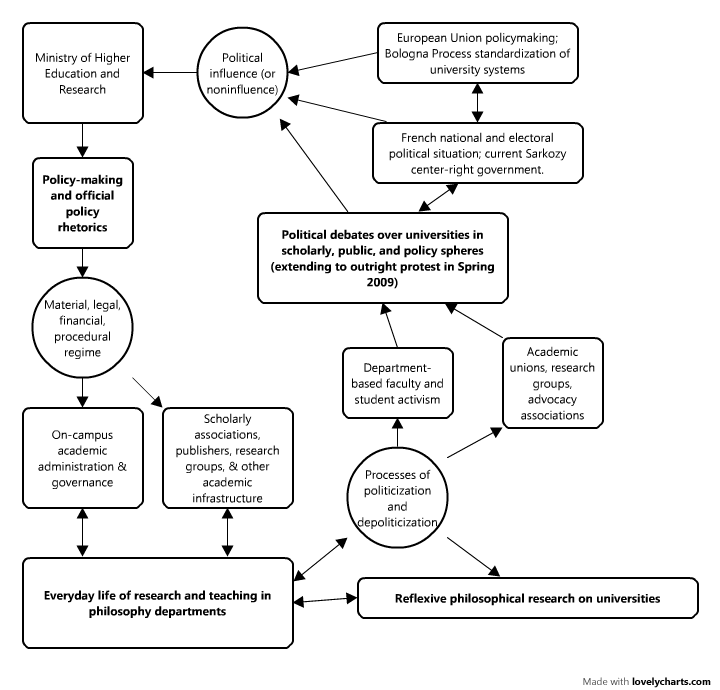

I started to feel that I’d been over-privileging the protestors in this blog, so I thought I’d translate a recent speech by the Minister of Higher Education and Research, Valérie Pécresse. Pécresse has had a controversial time in the Ministry and is now running for regional offices in Ile-de-France. This week she spoke at a conference at her Ministry, titled “Human Sciences: New Resources for Enterprise?” I couldn’t make the conference because the website said it was full and couldn’t accept further registrations, but I found the text online. Her speech was everything one could wish for — at least if what one wishes for is the best possible integration of universities into the work world.

I’ve been listening to the results of your debates with great interest.

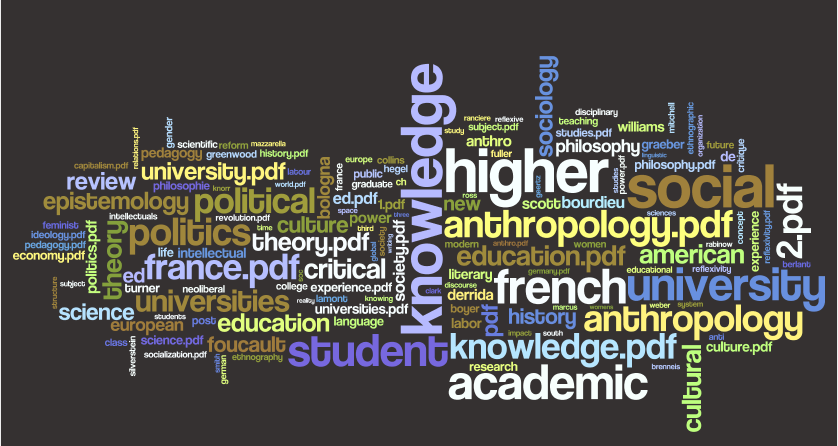

It’s remarkable that we’ve been able to bring students, young graduates, university actors and business representatives together for this debate on the “new resources for enterprise” that the human and social sciences represent.

The question that has been discussed here for the past three-plus hours is essential. It’s at the heart of my activities at the Ministry of Higher Education and Research.

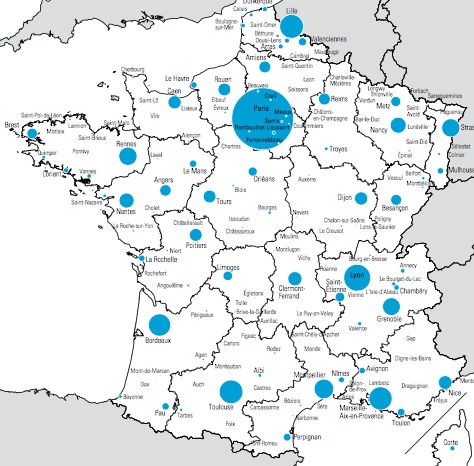

There was a time when, among employers, the universities had a bad reputation in relation to other establishments of higher learning. This time has passed. For almost three years now I’ve led efforts that aim to restore the universities to their full place in the country’s instructional programs.

Graduates in the human and social sciences deserve to be supported in their search for employment. To be sure, three years after the end of their studies, graduates with a license in classics, languages or history have unemployment rates around 7%, which is actually lower than those with the same degree in physics (8%) or chemistry (12%). But these encouraging statistics should not hide a worrisome reality: these fields also see a process of unacknowledged selection — by failure. This failure extends to as many as 50% of enrolled students, in both the first and in the second years [of the 3-year license].

For too long, we have let things be without reacting.

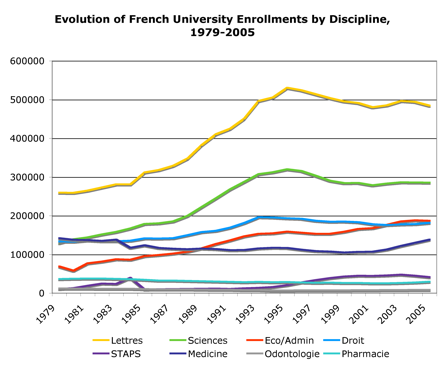

The fields of social and human sciences have welcomed many of the students coming from the second wave of massification of university enrollments, the one that began in the 80s. But the democratization of access to higher education has remained unfinished. We have too often neglected to support these new high school graduates. They have been driven by the system’s inertia [les pesanteurs] towards the social and human sciences, without really having chosen them.

It was in order to reverse these tendencies that the law of 2007 set disciplinary and professional placement [l’orientation et l’insertion professionnelle] at the heart of the university’s missions. The “License plan” has offered universities the means to bring students up to speed and to better prepare them to enter professional life.

It was not acceptable that many enrolled students never showed up to take their exams, nor that the university had such high exam failure rates. From this point forward, troubled students should be able to leave the university better armed for professional life. And, starting this year, universities should furnish their professional placement indicators.

In other words, students and students’ issues have been brought back to the heart of the university. Henceforth it will be possible to respond to their legitimate needs for disciplinary placement, for training [formation] and for preparation for professional life.

Continue reading “Pécresse, business and the human sciences”