Last Friday, as my last work event at Whittier College (since my postdoc contract is finishing up), I went to graduation. A few observations on graduation as seen from the faculty perspective seem to be in order.

Category: space

Bourdieu on UC Santa Cruz

I just came across Pierre Bourdieu’s curious comment on American universities and their set-apartness from society:

Whittier College at the end of summer

I grew up partly in a college town, and I’ve been around college campuses most of my life. One of my favorite times of year is this late-summer empty moment that happens after summer sessions finish and before classes start for the fall. It’s peaceful; you get a clearer view of the space.

Here’s what Whittier College looks like this time of year.

Philosophers without infrastructure, Part 2

Following up on my last post (and indirectly on a couple of older posts), I came across an interesting interview extract that comments in a bit more detail on the lived experience of being a philosopher with practically no work infrastructure. Here’s a philosopher from Paris 8 commenting on his workspace:

Professor: “I don’t think I’m giving you any scoop in saying that, on the material level, the Philosophy Department is the poorest one in the country. It’s clear — it’s very clear, even. When, for instance, young colleagues were arriving after I got here — at the moment I’m thinking of Renée Duval who sent me a message asking, so, where was her office [Laughter] although she didn’t have an office. And, you know, even at Paris 7, if you want to meet, I don’t know, Frédéric Gauthier, I say Frédéric Gauthier because we know each other pretty well, so, indeed, he will make an appointment with you in his office.”

A department secretary interrupts: “Still, they don’t have their own offices, they have a shared office for teachers.”

Professor: “Non non non non non non non. Gauthier, he has an office, and there are other offices. At most, they’re two to an office. Of course! No, here, it’s on the edge.”

Secretary: “Yes, it’s on the edge.”

Professor: “Yes, here, it’s borderline scandalous. Meaning that, for example, we wouldn’t have to be meeting here [in the staff office space].”

Secretary: “Mais non, I agree with you.”

Professor: “Mais oui. And, well, there’ll be an office, we would be in the office, indeed, we could both of us shut the door. So for example, the master’s thesis exams happen here [in the staff office space].”

Me: “Really, they’re here?”

Professor: “Yes, it happens — and so people who show up, we can’t prevent them, it’s the office — where they turn in their homework, where they come for information, but, still, it’s scandalous. The first year, when I came, throughout practically the whole first year, I spent the first twenty minutes of class with the students looking for a room. It’s since been stabilized, but—“

Continue reading “Philosophers without infrastructure, Part 2”

Philosophical lab infrastructure

The short version of this post: Philosophers have practically no lab infrastructure.

The long version:

Coming back to my research about philosophy departments in France, I was recently reading an institutional document describing the (highly-rated) research laboratory for philosophers at the University of Paris-8. Apparently it was a bureaucratic requirement to write a section describing the “infrastructures” available to the laboratory. But since Paris-8 is a typically underfunded public university, operating in cramped quarters on a small campus in the Parisian banlieue, the sad reality is that their infrastructure was quite limited. To the point of comedy.

I quote:

Infrastructures

L’unité dispose d’une salle de 35 m2, équipée d’un téléphone, de deux ordinateurs fixes et d’une connexion par WIFI. Elle est meublée de tables, chaises, et bibliothèques. Elle est située dans un bâtiment neuf de moins de deux ans. La surface disponible par chercheur membre de l’équipe à titre principal est de 1,5 m2.

The unit possesses a room of 35 m2, equipped with a telephone, two desktop computers and WiFi access. It is furnished with tables, chairs and bookshelves. It is situated in a new building less than two years old. The available surface per principle laboratory researcher is 1.5 m2.

One and a half square meters per researcher is just about enough to cram a chair into, and clearly not enough for any sort of individual workspace. Accordingly, there were none; the room in question was purely used to hold small seminars. The whole laboratory staff would never have fit inside it, and when they did have meetings, they took place elsewhere.

There is, of course, something charming about the plaintive note that at least the tiny room is “situated in a new building less than two years old” (the building pictured above). It’s as if the author felt obliged to put only the most positive spin on a clearly inadequate situation. Nevertheless, there is something to learn here about what counts as infrastructure for philosophers at Parisian public universities: in short, all the productive infrastructure (the books, the libraries, the computers, the desks) is elsewhere, generally at home, and the campus becomes purely a place of knowledge exchange, not of knowledge production. Which is why it it is possible to have a philosophy lab with practically no facilities.

New Years

Outside my new house, which is currently full of half-unpacked boxes and lamps waiting to be reunited with their shades, there’s a palm tree. If you go out and descend the fourteen steps from the front door, you’ll pass a series of low houses, and, finding yourself at the corner of a shady boulevard, you can arrive, after another minute, at a large sign reading Whittier College, where I’ve just started working as a postdoctoral fellow.

I got hired largely because I had a background in both anthropology and web programming. These past few years, while I was finishing my dissertation, I was also working full-time as a web applications programmer for the University of Chicago’s Humanities Division. Mainly I built administrative applications for them — internal software to keep track of student progress, keys, endowments, course scheduling, that sort of thing. I also worked on some research projects — Scrolling Paintings and the Digital Media Archive were the most interesting — and used a bunch of handy technology, like ansible, solr, ruby on rails, ember.js, drupal, shibboleth, LDAP, nginx, postgres, or redis. It was an unusual job, because a lot of universities don’t have in-house software development, but I learned a lot there.

In any event, my new job in Whittier is half in the Anthropology Department and half in the Digital Liberal Arts Center. This spring I’m teaching a class on digital cultures, and next fall, I’m thinking of teaching a class on anthropology of education, and another about web programming. And I’m working on a couple of book projects coming out of my dissertation — one’s going to be about the French faculty protest movement in 2009, the other about the Philosophy Department at Paris 8 — and hope to be able to blog much more regularly, at last.

Last day in Paris (2011)

I’m not sure whether this little descriptive passage from my fieldnotes will ever have much use in academic discourse, but it does remind me quite vividly of urban space in my fieldsite.

May 4, 2011. Last day in Paris. A man across from me on the metro dangles one hand in his crotch and texts with the other. A woman across the aisle is chewing gum and has flipflops with painted nails. The day is hazy, footsteps tap on the car floor, the train squeals as it accelerates; it picks up speed and the cement panels flash by and the advertising, CHOISISSEZ LE LOOK MALIN it says in orange on blue, hint of a smell of pastries, of sweaters, thrashing of the air through the open windows. I’m aboard the 14 train going to Saint-Denis to see a friend one last time; it sighs, the train, the man across from me now replaced by another, he rises, a woman gathers her purse, staggers a little as she gets off as the train shudders, with its long tube of fluorescent lights, with the grey of the car and the black of the tube that the tube of the train rushes along, rushes through; and I’m elbowed gently, but fortunately it’s not a période de pointe.

On Korean American students in Illinois

Continuing with my sequence of book reviews, I recently sent LATISS a review of Nancy Abelmann‘s fascinating 2009 book The Intimate University. It should be coming out in the new issue of LATISS; it reads as follows:

Nancy Abelmann’s The Intimate University is at heart a study of the relationship between a university and a social group. The university is the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign; the group is that of Korean American students hailing from the Chicago area; and the relationship between them, as Abelmann effectively demonstrates, is tangled up in contradictions. Foremost among these is the matter of race; the Korean Americans she studies are caught in the bind of being an American model minority. They are not white enough to comfortably enact the American fantasy script of a universalist (but implicitly white and affluent), liberal, liberating and “fun” higher education, of a kind that would license “the luxury of ‘experience'” or a freedom from immediate vocational concerns (10-11). But they are “too white” and too affluent, from the point of view of national ideology, to comfortably identify with the nation’s oppressed racial groups. This implies a fraught relationship with other groups — one student describes her “bad impression” of “weird,” implicitly African American break dancing in one Chicago suburb (28) — but also a powerful “compunction to dissociate” from stereotypes of Koreanness, particularly with the Korean instrumentalism and “materialism” they associate with their petty-bourgeois immigrant parents (161, 7). This disidentification with their own group — or at least with its more problematic typifications — is, as Abelmann emphasizes, the product of a malicious American norm that identifies full individuality with whiteness, and ethnicity with groupness (161-2).

Politics that fade

I happened to discover the other day that if you display photographs from my fieldsite at full vertical resolution, while reducing the width, you get a vertiginous sense of height. This here was the light of late afternoon as it fell through low bushes across the windows of an amphitheatre in Bâtiment D (D Building) at Paris-8.

I was struck by the grain of the windowpanes and the gravely complexion of the sunshine. The date was April 14, 2010. The occasion was a debate over the university’s impending transition to “expanded competences and responsibilities,” responsabilités et compétences élargies, which is French bureaucratic jargon for the transfer of various managerial functions (like human resources management and accounting) from the national Ministry of Higher Education to the local campus administration. In short, it is a sort of managerial devolution, wherein formerly centralized bureaucratic functions are removed from the national level and transferred to the local level. This process was mandated by the Sarkozy government’s controversial 2007 university law, the Loi Pécresse or LRU, and since Paris-8 was a center of opposition to this law, the transition to the new managerial regime was controversial on campus.

An elongated view of the center of the amphitheatre shows the windows carved high up in the walls, the central dais with the President in his suit surrounded by his counselors, the vertigo of looking down at him over the cascade of desks and the cascade of hair and the scattered ranks of faculty and staff, the monotonous lines of critical leaflets that had been put out on the desks before the meeting to sway over the crowd, the many empty desks and seats that reminded us that, in the end, only a tiny minority of faculty, staff or students would bother to attend an event like this one. (To be fair, it was a relatively well-attended event, but nonetheless the room was mostly empty.)

In a professor’s house

Earlier this fall I wrote to someone I’d met at Paris-8, a professor, to ask if we could meet and talk about campus politics. “Actually I just dropped out,” he said. (By which he meant “retired,” though it was in difficult institutional circumstances.) “But you’re welcome to come visit me in Brittany,” he added. Not that many French academics have invited me to their homes, so I was happy to accept, and last weekend I managed to get there in spite of the nationwide rail strikes.

Here I just want to show you a little of what the house looked like.

Seen from the quiet back street where it sat, the house looked conventional enough, with a solid stone façade, high windows with the obligatory shutters, a witch’s hat of a gable.

If we look in through the garden gate, though, we can see that the garden is decidedly non-Cartesian, the path is narrow, the entrance bowed over with branches. The garden is a protected space, walled off, the plants preserving the boundaries of private life.

If we go farther into the garden (these next few pictures were from the next day, which was cloudy) we see that the space doesn’t open up into a large open lawn, but rather is divided into little areas with different things, the bush that shelters the bicycle trailer, the path that’s edged by a long clothesline, a brushpile higher than your head.

Continue reading “In a professor’s house”

The art of the student toilet

This post will make for a strange contrast with the last one, since we move from looking at the most noble of French spaces to the most profane. As I’ve mentioned before, I’ve had the privilege and burden of living in a number of short-term apartment situations here, and in the shared student apartment where I lived last month, I was amused to discover that the tiny room housing the toilet had become the most elaborately decorated room in the house.

This ought to give you the general idea. The other wall and the inside of the door were no less decorated.

Beside the chain that flushed the toilet tank, there was a little user’s guide. “Please flush the toilet with the softness of an old lady. Thanks!” (This incidentally is also a fairly characteristic example of French cursive handwriting.)

A lot of the decoration was concert announcements and seemingly random images.

Continue reading “The art of the student toilet”

In the Minister’s office

Last weekend, under the auspices of a program called European Heritage Days, I went on a tour of the offices of the Minister of Higher Education. I’ve been in the building before for various academic events, but, unsurprisingly, the part that has the Minister’s office is separate from the part that ordinary visitors usually see.

This gate isn’t normally open to the public. There was something vaguely contradictory about the staff’s relation with the public, like in an art museum where they’re there to smile at you but also to protect the place against you. At this gate, two people stood watch in suits: one of them was radiant and tried to persuade every passing person to come visit; the other (back to the camera) seemed silent and kept watch.

Farther inside the premises, there were security guards stationed at every corner. I suspect that they don’t patrol that heavily on usual days, since the workers seemed unfamiliar with each other. I overheard one guard asking another, “What was the name of that guy downstairs, again?” “Umm, no idea.”

This, the building where the Minister has her office, is what I would describe as standard French government architecture. Pale stone, French and European flags. Leaping arches, solemn columns. The decoration is more than merely functional, but not ostentatious.

The first room you saw inside was this, apparently a place where they hold press conferences and the like. I noticed that the decor combined very traditional features like a parquet floor and a chandelier with very businesslike, modern features like a tiled ceiling and little spotlights. I guess that’s how you try to be modern while retaining the aura of past forms of architectural dignity.

Continue reading “In the Minister’s office”

Geometrical space in French universities

Looking back at my photos of Toulouse 2-Le Mirail, I’m struck by a common visual trait: the sheer repetition of cartesian grids in academic space.

The very tiles on the walls are gridded.

The bars and grills of the windows recede along their grid towards an unreached vanishing point.

In a courtyard at Toulouse, the pillars run in rows. The cement beams run in columns. The bench has a predictable railing. The windows are little boxes of crosses. The grass is boxed in. The one curved cement beam in the open ceiling only serves to set off the space’s overall linearity.

The chairs and desks are in alternating rows, their regularity still evident even if we look at them from an angle.

One starts to wonder if the campus was designed to make the individual feel a sense of vertigo in the face of the endlessness of this rectangular tunnel. The plane of the ceiling, broken up into a vast set of cement indentations, mirrors that of the tiled walkway. The sides, admittedly, are less regular, but even there we see regular columns, symmetrical pathways leading off on both sides.

Nonexistent academic neighborhoods

There have been a bunch of articles on the borders of campus spaces. One thing they all have in common is an insistence that universities in some way manage their boundaries, and usually the surrounding neighborhoods too. People have chronicled how universities put up fences to keep out the poor, how they tinker in urban redevelopment, how they build science parks and sometimes fail, how they create low-income college slums and low-budget small businesses like copy shops, and so on.

But when I was visiting Aix-en-Provence last month — its iconic mountain is shown above — I was struck by the sense that the university just didn’t have a neighborhood. Sure, there were a couple of little sandwich shops and a café where the faculty ate lunch. There was a complex of dormitories on a hilltop and a nearby park where it looked like a lot of students were enjoying the sunshine. There were streets where you could see students and even a few teachers hurrying towards class. Nonetheless, in some directions you only had to walk a dozen yards from the campus gate before the university was entirely forgotten in the quiet streets.

Here, then, as a supplement to the scholarly research that has demonstrated the existence of campus boundary zones, I want to write about a few photos I took that illustrate the relative nonexistence of the campus neighborhood.

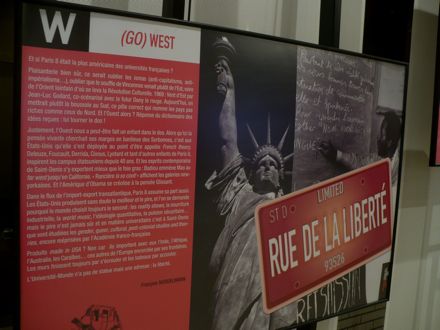

The most American of French universities

In this winter’s exhibition on the history of Paris-8 at Vincennes (the university’s first site in the 70s), I was particularly interested in a text that discusses the relationship between Paris-8 and U.S. academia. The exhibit was separated into panels each starting with one letter of the alphabet, and this was one of the last of them: “W – Go West.” François Noudelmann, the author, kindly gave me permission to post a translation. So without further ado:

W — Go West

And if Paris 8 was the most American of French universities?

Just kidding, of course: that would be forgetting all the isms (anti-capitalism, anti-imperialism, …), forgetting that Vincennes’ breath comes instead from the East, or even the far East where the Cultural Revolution rose up. 1969: East Wind by Jean-Luc Godard, co-written with the future Dany the Red. Today the compass would be set South instead, towards that pole that defines non-rich countries in terms of the North. And as for the West? The response from the dictionary of received ideas would be: turn your back on it!

But the West may thus have taken advantage of us without our knowing it. While here new ideas [la pensée vivante] are forced to settle in the margins on the outskirts of the Sorbonne, in the United States they have grown so far they have their own label, French theory. Deleuze, Foucault, Derrida, Cixous, Lyotard and so many other children of Paris-8 have inspired American campuses for the past forty years. And the contemporary minds of Saint-Denis are exporting themselves faster than foie gras: Badiou brings Mao to the far west in California. “Rancière is so cool!” New York galleries announce. And Obama’s America creolizes itself with the thought of Glissant.

In the flux of transatlantic import and export, Paris-8 too plays its part. The United States no doubt produces the best and the worst, and one wonders why the world always chooses the latter: the reality shows, the industrial food, the world music, the quantitative ideology, the drive towards security… but the worst does not always come to pass, and when it comes to academic matters, Saint-Denis is the place where people study gender, queer, cultural, post-colonial studies and theories, which are still distrusted by the mainstream French [franco-française] academy.

Are they products made in the USA? No, because they bring with them India, Africa, Australia, the Caribbean… these others of a Europe encircled by its borders. Walls always end up crumbling and ships always come to birth.

The University-World doesn’t have a statue, but it does have an address: liberty.

Occupied “free space” at Paris-8

For about two weeks this month, a large space by the entrance to Paris-8 was occupied by students. It had formerly been a coffeeshop operated by a private company, but had been closed months or years ago.

To enter after hours when the campus was supposed to be closed, you had to climb up on that chair and through the window and down a little stepladder on the far side.

One of the occupants’ favorite activities was decorating the walls of adjacent university buildings. This wall was, as far as I recall, pretty much blank before the occupation began; the slogans now read “Bureaucrats outside!” “McDonald’s, we’ll burn you.” “State Rabble.” “Screw the government’s cleansing system before it screws you.” “Riot!” “Fuck may 68, fight now!” “Anti-France” (I have no idea what this one means, by the way). “Drops of sunshine in the city of ghosts.” “Long live the canteen and worker’s self-management” [this refers to a recent campus event I can only describe as student-organized Food Not Bombs for undocumented workers]. “Popes, popes, popes, yes. But nazi and pedophile popes?” “Burn the prisons, destroy the immigration detention centers.”

We can deduce from this photo that someone had invested in numerous colors of spraypaint.

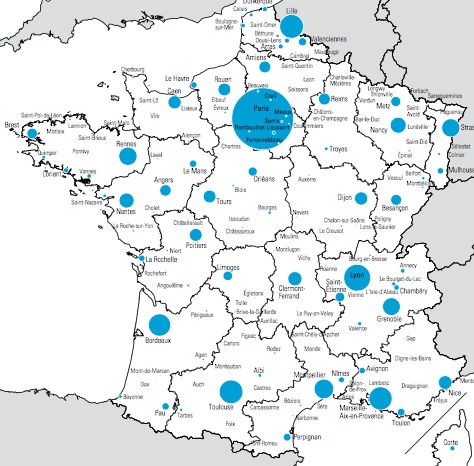

French university towns and decentralization

As it turns out, there’s no need for me to cobble together my own maps of French higher education. A beautiful official atlas is already made available by the Higher Education Ministry, with far more detail than I would care to track down by myself. Let me reproduce a couple of their figures:

As you can see, Paris is still by far the biggest university town. If we look at the accompanying figures for 2007-8, it turns out that Paris proper has 156,743 university students, with 320,942 total in the Paris region (Ile-de-France). After that, we have Lyon (73,262), Lille (58,788), Toulouse (57,907), Aix/Marseille (56,590), Bordeaux (53,335), Montpellier (43,355), Strasbourg (37,299), Rennes (37,008), Grenoble (32,978), Nancy (28,078), Nantes (26,329), Nice (21,664), and from there on down… As in the last post on centralization, here too, mapping by student population size, we can see that the Parisian region remains by far the largest university site — its 320,942 of 1,225,643 total public university students comes out to 26% of the nation’s university population. (Note that universities only constitute about half–56%–of the French higher ed population, but we’ll talk about the rest of them some other time.)

But our thinking about centralization has to shift when we find out that, over time, provincial universities have grown and thus diminished Paris’s relative standing. In other words, it seems that historically, Paris used to be even more the center of the academic universe than it is now. To better understand this process let’s look at a thumbnail sketch of French university massification by a sociologist I know here, Charles Soulié:

Continue reading “French university towns and decentralization”

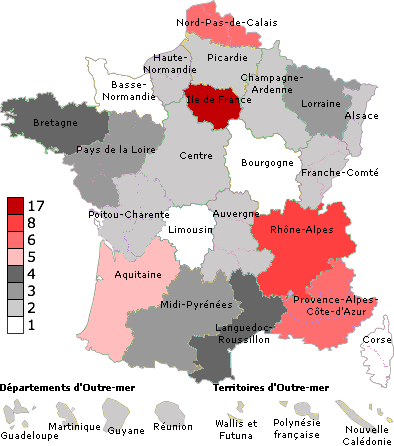

Geographic centralization of French universities

It is a famous, even infamous fact about French universities that the system is deeply centralized, and centered on Paris. But over the years the university system has diversified and there are now 83 French public universities (of which 5 are in Corsica and the overseas territories). However, as every French academic would surely attest, the system remains deeply Paris-centric. For the foreign reader, I thought it would be helpful to present a little map of the density of universities by region (based on this original):

Continue reading “Geographic centralization of French universities”

Paris-8 by the light of different days

This is the university where I do my research, this year. I like this picture because it has nothing, nothing, nothing to do with the overdetermined and crass narratives that so easily predetermine one’s whole perception of this campus space. This is the tree that has grown up behind the amphitheatre with its jagged roof, the arms of the branch entirely geometrically incompatible with the sawtooth linearity of the dark building. There’s nothing here about politics, nothing here about pedagogy, this picture contains no academic knowledge, it embodies no concept unless you count the concept of mute visual juxtaposition of organic and inorganic form. There’s no knowledge in this picture, no sociality, no people, no conversation, no texts, no pedagogy, no politics, no record of human activity besides the roof built to some absent architect’s scheme. It’s autumn but you wouldn’t know that except from a couple of tiny leaves that gleam yellow in the underexposed daylight.

Continue reading “Paris-8 by the light of different days”

The origins of university real estate

A friend of mine recently asked if I knew anything about the history of the college quad as a place of free speech and debate. I didn’t, but I’ve done a tiny bit of research in the last couple of days and the results are interesting. Among other things, I observe something of a historical transformation in the scholarly literature: an older era’s work concentrated mainly on college architecture as an aesthetic form in itself, tracing the origins of campus buildings and the progress of architectural styles. Many campuses have their own histories; they are often adapted to the rhetorical needs of campus self-promotion and self-consecration, the sort of thing written by loyal emeritus professors to please the president. On the other hand, a more recent, more modern, more critical literature takes up a different problem, that of the university’s relation to its town, to its broader environment, to its social context; this research tends to be darker, looking at university’s sometimes problematic involvement in urban development, in racial exclusion, in slum clearance, in gentrification. I’ve posted before about Gordon Lafer’s history of Yale urban development and about Kate Eichhorn’s paper on the “abject zone” of copyshops around the University of Toronto — typical examples of this more recent literature.

I have a bunch of photographs of university quads to look at here, and some more recent articles from the U.S. context to think about, but to start off this new set of posts I wanted to begin with this extract from a History of the University in Europe. It offers a very suggestive picture of how universities began to acquire real estate in the first place:

“In the late Middle Ages, as student populations grew and universities ceased to migrate, universities acquired buildings and movable property. For a long time time in Paris and Bologna the administration had not needed to take care of buildings, because there were none. Lectures were held in houses rented by the masters, examinations and meetings in churches and convents. In Paris, however, both the theological faculty and the nations began renting property as early as the fourteenth century, and acquiring it in the fifteenth century. With lecture halls in the rue de Fouarre and many other places, with colleges and lodgings, and with churches (all of them on the left bank of the river), the Quartier Latin became the university quarter of Paris. The young Bologna studium, too, contented itself with private houses and religious or public buildings for lectures, meetings, and ceremonies.

Growing numbers of students, some of them very young and needy, made housing facilities more necessary as time passed. College buildings arose everywhere, but especially in universities with large faculties of arts, such as Paris, Oxford, Cambridge, and later on the German universities. Italian studia also looked for lodgings for their students. The comparatively few colleges in northern Italy were founded in and after the fourteenth century, at first in converted private homes. After 1420 a special type of building appeared, the domus sapientiae (house of wisdom) or sapienza, a teaching college modelled on the Collegio de Spagna in Bologna, built in 1365-7. The rooms were grouped around an arcaded courtyard. Gradually the sapienza ceased to be dwellings and in early modern times became the official university buildings with lecture rooms, discussion rooms, a library, rooms for accommodation and administration, archives, and a graduation room. The palazzo della sapienza became the current name for these sumptuous university buildings. (136-7) Continue reading “The origins of university real estate”

Universities on strange premises

It has slowly dawned on me that a huge number of universities came by their premises, by which I don’t mean their philosophical axioms but their physical environments, in exceedingly peculiar ways. Some of what follows below is hearsay and I don’t really have time to do historical research. But there’s more odd variation here than one might have predicted.

- The Danish School of Education occupies a building that, I’m told, was during World War II the Nazi museum of Scandinavian folk cultures. (This apparently had something to do with creating an Aryan heritage, though I gather that Germans at the time were hard pressed to pass themselves off as more Aryan than the Scandinavians!)

- Cornell University: Was once a farm (albeit financed by the massive business success of Western Union’s telegraph operation in the 1850s). University of Connecticut: likewise was once a farm.

- The University of Paris-8 used to be in Vincennes but was forced to move to Saint-Denis in 1980, and all its original buildings were demolished on the government’s pretext that it was a den of drug dealers (according to a film I saw).

Militant student slogans and iconography in Toulouse

Last week while I was in Toulouse, I went to take a look at the local university (Mirail), to see if it turned out to be the one in the video I posted about last week. And indeed there were a large number of decrepit buildings, occasionally graced by lovely flowers. But the buildings also turned out, like Paris-8, to display an intense activist visual culture: of graffiti, of slogans, of icons, of murals, of messages that contradicted each other, of clashing color.

No to the LRU! says a figure falling into a trash can. Or is it the LRU itself that’s falling into a trash can?

“For a critical and popular university [fac]!” Apparently this is a traditional militant slogan at Toulouse.

“Get a new slogan please!” is the caption written below by someone who apparently disagrees or is simply bored.

[La fac, i.e. la faculté, is a now bureaucratically obsolete term that used to designate a college, a faculty, a division – as in the Faculty of Arts, the Faculty of Law, etc. It is still used in common parlance to refer to the public universities – les facultés – as opposed to other institutions of higher learning (private business schools, elite government institutes, and the like).

“For a hard and copulating university!”

Continue reading “Militant student slogans and iconography in Toulouse”

Notre belle université

A few months ago, Baptiste Coulmont posted a sarcastically titled video called “our beautiful university” that testifies to the squalor and physical deterioration of a university campus in the south of France, Marseille or Toulouse I think. It’s essentially a youtube montage of photos of decrepit university spaces; the photos are also collected at Picasa.

At times, the mold approaches the complexity of mountaintop lichens, or perhaps it’s more like a spontaneous display of abstract art.

Visual culture and institutional difference: Paris-8 & the Sorbonne

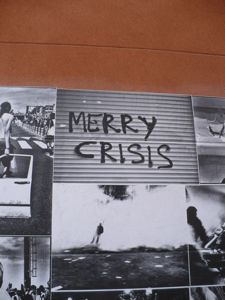

A sudden piece of English text inserted in the middle of an exhibition of political photographs at my field site. Paris-8. A charming metacommentary on global reality. Merry crisis!

If you wanted to describe this image in the most basic descriptive language you could say: this is a photo of a photo of a graffiti tag set among other photos, photos of people bloody in protests, of police in riot gear lines, of people running and throwing things, of people invisible in showers of light. See that flood of white in the photo immediately beneath Merry Crisis? With the figure askew and silhouetted? I have no idea what that is. But I do comprehend that this is a collage of leftist protest culture, aestheticized in the genre of an art photo exhibition, and further recontextualized in the form of political statement attached on the outside of Paris-8’s Bâtiment B2. Paris-8 is a university with an enormous visual text taped and sprayed across its walls. Campus buildings frequently have deteriorated walls, just from the sheer number of signs (affiches) that have been put up and torn up and torn down. It’s the kind of place where images, like this one, are not only compound visual objects (referencing other visual objects and visual genres), but are units in an overwhelming student reappropriation of academic space, a culture of defacement of the corridors that someone jealous of property rights might call vandalism with a political alibi.

This defacement has limits, though, being essentially restrained to surfaces within arm’s reach of the ground. The buildings themselves tell a different story.

Continue reading “Visual culture and institutional difference: Paris-8 & the Sorbonne”

Commodification of the sacred in campus landscapes

Kind of amazed to read this article, “The Power of Place on Campus,” by one Earl Broussard, in the Chronicle of Higher Ed (temp link). Striking because it is so obviously a further step in the marketization of every aspect of campus life. The sacred is invoked as a new fund-raising activity. Is this what happens when anthropologists decide to become consultants to college administrators? Broussard writes:

Colleges and universities should never underestimate the power of special, transformational, and even sacred spaces on their campuses… Universities are products of history and tradition. Not only are they institutions of scholarly learning, but they also are sites of memory and meaning, with cultural spaces that have played host to decades or even centuries of ritual.

…Such transformational places with unique emotional resonance have an almost sacred nature. The word “religious” comes from the Latin verb religare, meaning to bind or reconnect. Thus, anything that reconnects us is, inherently, a deeply personal or spiritual experience that has great meaning — and the university campus is ripe with opportunities for people to reconnect.

…Elite universities understand the importance of branding in creating long-lasting loyalty among students, and they use very specific and often-repeated images in such efforts… such imagery typically has very little to do with dormitories, classrooms, libraries, or students working late into the night. Most images focus on the campus as a landscape, with views of special buildings, students walking or lounging on an open green, and, of course, football players or bands performing on the stadium’s holy ground.

So the sacred spaces on campus are something to be branded. Something to be created as a spectacular image that will produce “unique emotional resonance,” that will give us a “deeply personal or spiritual experience that has great meaning.” This Orwellian language deserves, I think, to be stood on its head: “unique” here really means “totally generic,” and “deeply personal” amounts to “totally determined by cunning advertisers.” For there is after all nothing personal in a pre-scripted contact with the sacred, except through the medium of delusion.

Continue reading “Commodification of the sacred in campus landscapes”