This post will make for a strange contrast with the last one, since we move from looking at the most noble of French spaces to the most profane. As I’ve mentioned before, I’ve had the privilege and burden of living in a number of short-term apartment situations here, and in the shared student apartment where I lived last month, I was amused to discover that the tiny room housing the toilet had become the most elaborately decorated room in the house.

This ought to give you the general idea. The other wall and the inside of the door were no less decorated.

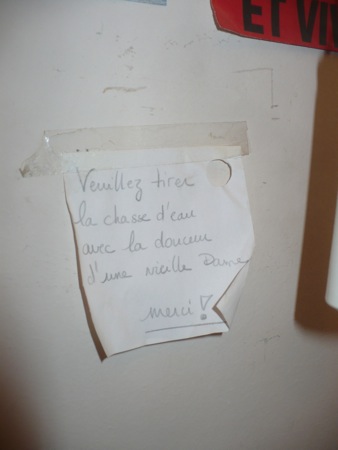

Beside the chain that flushed the toilet tank, there was a little user’s guide. “Please flush the toilet with the softness of an old lady. Thanks!” (This incidentally is also a fairly characteristic example of French cursive handwriting.)

A lot of the decoration was concert announcements and seemingly random images.

There were also some mock-political slogans. “Work less to earn less and live better” (travailler moins pour gagner moins et vivre mieux) is a parody of Sarkozy’s “Work more, earn more” (travailler plus pour gagner plus). Interdit d’interdire? takes a bit more explanation: it translates as “Forbidden to forbid?” which is a famous 1968 slogan, but obviously the joke is that it’s juxtaposed with an image of a smoking smileyface, as if to say: you don’t seriously want to forbid forbidding something as unhealthy as smoking, do you, radicals?

Some essential technologies for hygiene and body care: toilet paper, air freshener, a radiator for the winter. (I know someone out there is going to be saying: what is the point of anthropology if the best it can do is tell us that the French use toilet paper? To which I reply: As an anthropology blog, part of the goal is to remind us that what’s taken for granted one place is nonetheless far from universal. Laura Pearl Kaya reports that in Irbid, Jordan, for instance, toilet paper is “an amenity generally considered disgusting… and rarely found outside of tourist hotels” [2009:263]. Even in France, as every tourist knows, a toilet seat is far from universally supplied, particularly in public toilets.)

If we look more closely at the art next to the toilet paper, we see a postcard entitled “The world as seen by the French.” The different parts of the world are labeled as follows. Europe: “Euroland.” Russia: “Bigger drinkers than us.” Mongolia: “Lots of emptiness.” Eastern Siberia: “We’ll never be going that way.” Turkey/Middle East: “Scary zone.” India: “Lots of little people.” China: “Cause of all our woes.” Japan/Philippines: “Live animal eaters.” Australia: “Very far away.” Mauritius: “Little piece of France very far away.” North Africa: “Former colonies.” Sub-Saharan Africa: “Incomprehensible zone.”

Antarctica: “Terra incognita.” Southern tip of South America: “Home of Nicolas Hulot” (who’s apparently an environmental activist). Brazil: “Machucambos Country (indian musical groups).” Colombia: “Wicked FARC.” Guadeloupe: “Little piece of France very far away.” America: “New friends.” Canada: “Incomprehensible cousins.” Somewhere in the Arctic: “Santa Claus’ Country.”

I won’t get into a long commentary on this little image, but suffice it to say that it falls within the genre of this kind of maps; it involves a deliberate use of national self-stereotyping; and it invokes an interesting sort of national surrealism. It’s tacitly saying, in other words, that every nationality has its own, inevitably distorted, inaccurate, hyperbolic way of looking at the world. And it’s interesting to me that even in a space as tiny and enclosed and private as this toilet there’s an image of the world. As if even the smallest, most confined, most ostensibly instrumental and even profane spaces sometimes find themselves becoming scenes where the world gets presented as a totality.

Here at right we have the one potentially controversial image in this whole series: a silly photo of scantily clad men in towels labeled “Gay Saturday at The Baths.” I was ready to just accept it as one of the larger series of silly images, but soon after I moved in, one of my two (former) roommates made a point of saying something like, it’s not me who put that one up, don’t get worried, it’s just a joke or something like that. To make the most blindingly obvious interpretive comment about this, we see here that certain representations of sexuality are potentially threatening to the heteronormativity that pervades Parisian male youth culture, and hence evoke moments of boundary maintenance like this one. The message apparently being: Don’t worry, no one’s gay here. I guess if you wanted to meditate about this further, you’d have to think about how sexuality, privacy, intimacy, and bodily functions all get wound up together in spaces like this one.

I liked this poster, which is for the French publisher (called l’école des loisirs) of Where the wild things are.

Obligatory Beatles poster. To me, what’s interesting about it is its visual composition: we have here not just an image but an image of images, a compound image.

And to make matters even more analytically curious, I discovered that this particular toilet is — as ridiculous as it sounds to say this — a kind of reflexive space, a space that reflects back on itself, a space that represents itself to itself. Because on the back of the door was a photo of this very same toilet — presumably taken at the beginning before anything was put up on the walls. An image of toilets past, I suppose.

There were a bunch of other images of this apartment, of the roommates hanging out together, and of their living spaces. These two were photos of the living/dining room: a series of representations of the apartment itself as a domestic and social space. Of course, everyone including me has now moved out, so all this is gone now. They hadn’t found new tenants, so the place is probably sitting empty at this very moment, as I write.

I just want to end with a couple of broader observations about toilets. As American anthropologists recall from Horace Miner’s Body Ritual among the Nacirema, the (Western) toilet is a deeply profane space, and — as Miner observed fifty years ago — “excretory functions are ritualized, routinized, and relegated to secrecy.” That mostly holds true for France (with the major exception of male public urination, which is very widespread). Admittedly, there’s a whole economy of toilets here: there are people who make their living as public toilet attendants, collecting something like 35 cents from each visitor, and Paris famously has these peculiar self-cleaning public toilets scattered throughout the streets. Far from being totally private spaces, the shared public toilets create boundary zones between public and private, between physical intimacy and social distance. But they’re still deeply instrumental spaces, toilets: one associates them with what one can call in English “bodily functions” or in French, apparently, “faire ses besoins” (roughly, doing one’s needs). Which is why it becomes anthropologically interesting that a toilet would get so decorated, becoming as much an aesthetic space as a place for pure corporeal functionality. Along with the visual art, for that matter, there was an enormous pile of newspapers, which indicates that certain of my roommates spent long periods of time in this small space.

What does all this have to do with universities, you ask? Well, first of all, as a room in a student apartment, I reckon it falls under the broader rubric of “student culture” and hence deserves our attention. (Two of the three long-term residents here were students; the third was a recent graduate.) Indeed, universities themselves have toilets — ones which, in the badly underfunded French university environment, have sometimes become cause for consternation. So in a purely empirical sense, I’d point out that even the little temples of “bodily functions” constitute part of the institutional and social arrangements of academic culture.

But beyond that, it seems to me worth recalling in closing that, if it seems particularly inane to comment on toilets in connection with universities, that in itself is only a sign that we still live in a world built around a deeply felt opposition between the “higher” life of the mind and the “lower” needs of the body. I guess the hyperbolic way of putting this argument would be: there could be no universities if there were no toilets. Partly that’s just for simple biological reasons, of course. But it’s also true inasmuch as the cultural divide between mind and body — which the university embodies institutionally and draws on conceptually — would simply make no sense if there were no embodiment of the lowest and most corporeal side of things. For the university to be a very highly valued cultural institution, there must also be a very disvalued and stigmatized cultural institution to stand in opposition.

Seriously, though, I’m half kidding.

Haha, Nicolas HULOT and (very) South America: it is related to a well known former french TV broadcast, titled… “Ushuaia” !

In this broadcast, N. Hulot performed a number of sports, some of them somehow bizarre, and burned huge quantities of petrol ;->

Later, he converted himself to Ecology ;-)))

I may be wrong, but i think that the “Little piece of France very far away” may not be Mauritius but Reunion island which is a french territory.

Funny article btw ! 🙂

Bonjour Webjunkie, oui, là vous avez bien raison!

I stumbled on this blog post because Inside Higher Ed linked to it and now I’m going to add your blog to my RSS reader. This was a fascinating and fun post and a nice little introduction to your writing on the blog in general (though I realize it’s not always so whimsical).