In this winter’s exhibition on the history of Paris-8 at Vincennes (the university’s first site in the 70s), I was particularly interested in a text that discusses the relationship between Paris-8 and U.S. academia. The exhibit was separated into panels each starting with one letter of the alphabet, and this was one of the last of them: “W – Go West.” François Noudelmann, the author, kindly gave me permission to post a translation. So without further ado:

W — Go West

And if Paris 8 was the most American of French universities?

Just kidding, of course: that would be forgetting all the isms (anti-capitalism, anti-imperialism, …), forgetting that Vincennes’ breath comes instead from the East, or even the far East where the Cultural Revolution rose up. 1969: East Wind by Jean-Luc Godard, co-written with the future Dany the Red. Today the compass would be set South instead, towards that pole that defines non-rich countries in terms of the North. And as for the West? The response from the dictionary of received ideas would be: turn your back on it!

But the West may thus have taken advantage of us without our knowing it. While here new ideas [la pensée vivante] are forced to settle in the margins on the outskirts of the Sorbonne, in the United States they have grown so far they have their own label, French theory. Deleuze, Foucault, Derrida, Cixous, Lyotard and so many other children of Paris-8 have inspired American campuses for the past forty years. And the contemporary minds of Saint-Denis are exporting themselves faster than foie gras: Badiou brings Mao to the far west in California. “Rancière is so cool!” New York galleries announce. And Obama’s America creolizes itself with the thought of Glissant.

In the flux of transatlantic import and export, Paris-8 too plays its part. The United States no doubt produces the best and the worst, and one wonders why the world always chooses the latter: the reality shows, the industrial food, the world music, the quantitative ideology, the drive towards security… but the worst does not always come to pass, and when it comes to academic matters, Saint-Denis is the place where people study gender, queer, cultural, post-colonial studies and theories, which are still distrusted by the mainstream French [franco-française] academy.

Are they products made in the USA? No, because they bring with them India, Africa, Australia, the Caribbean… these others of a Europe encircled by its borders. Walls always end up crumbling and ships always come to birth.

The University-World doesn’t have a statue, but it does have an address: liberty.

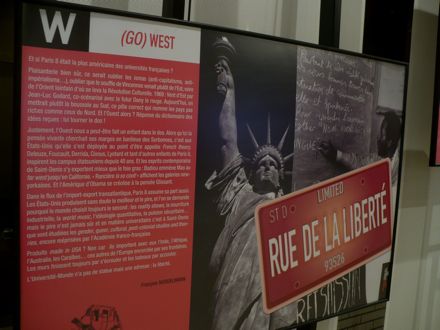

I suppose I should start by clarifying a few references. The “University-World” is the current official slogan for Paris-8, a concept-slogan that draws on the large fraction of foreign students at the university. Historically, it’s been a radically left-wing campus, hence the significance of the orientation towards the formerly socialist East. The university is currently located in Saint-Denis (if you haven’t picked that up from my earlier posts). And in Saint-Denis, the university’s mailing address is on the Rue de la Liberté, which is used here in the last sentence to amplify the consonance between the United States and Paris-8.

Now, I have to tell you that this text would come across as pretty counter-intuitive to most French readers. American universities in France are pretty often pictured as the incarnation of pure neoliberalism, of entrenched business influence, of massive structural inequality between rich and poor. In that light, it’s a bit of a shock to see the American university portrayed here mainly as a bastion of intellectual progressiveness, as the home of new ideas, of the “French Theory” of Deleuze, Foucault, Derrida, Cixous & Lyotard, of what Noudelmann called la pensée vivante, literally living thought. That goes against the stereotype.

Of course, and this is what I like about the text, it has some interesting ambivalences in its characterization of nations. France is cast as at once the bastion of a conservative, quasi-nationalist Sorbonne but also as the home of Paris-8, the radical institution from which much French Theory is said to have come. The United States, for its part, is painted as “producer of the best and the worst,” its trashy culture industry clashing with its intellectual openness. On the other hand, Noudelmann’s ambivalence about the U.S. is hardly identical to his ambivalence about France. One notes a certain asymmetry: France never appears here as a definite entity, but only as a cultural and institutional context designated by the adjective French. The United States is on the other hand made into an entity by being called by name. It’s as if France’s contradictions were spread out spatially and institutionally (the Sorbonne appearing, for instance, as the locus of conservatism), but the United States’s contradictions were condensed into one being.

The key conceit of the text, given the France-USA opposition, is to make Paris-8 into the key mediating figure between France and the United States. The U.S. appears here at moments as a massively magnified projection of Paris-8’s intellectual life. One wonders, of course, whether Noudelmann isn’t a bit overly optimistic about the life of French Theory in America. Many would argue that it became a radically apathetic, professional-intellectual commodity in its passage to the American humanities. I can certainly testify that the link between French radical thought and social movements, precarious even here, is dramatically more absent in the United States, so that there’s an effect of political deracination in reading, say, Foucault. And, of course, Paris-8 as a mediating institution is far from being without contradictions. A full analysis of this text would have to examine what it means that the text was displayed in an exposition on the history of Paris-8 that was derided by students as being an excuse for the past generation to relive their past radicalism in the glossy form of an exhibit. (I’ll have to come back to the exposition another time.)

In a way, this text is a commentary on the way that political space is nationally marked. At the start of the text, the (once socialist) East opposes the (emblematically capitalist) West, leaving France is somewhere in the middle. But by the end of the text, Europe is cast as a walled global center, encircled by its post-colonial others (Africa, India, the Caribbean) whose intellectual presence in France is thanks to their passage through the USA, where post-colonial studies has been more successful. In this later passage, the USA is cast as a point of intellectual mediation between Europe and the postcolony. I’m not sure what to make of this, to be honest, though it’s a good reminder that any understanding of French politics would seem to demand a fairly complex account of spatial metaphors.

There’s something to be said here about style, too, about the sly turns of phrase (not all of which I very adequately translated), about the sense of a continuous stream of thought created by the narrative’s twists and turns (is Paris-8 the most American of French universities? No! Unthinkable! And yet… And yet…). There’s something to be said about the paradox of a text that describes the globalization of ideas in a language that’s so full of local references as to be barely translatable (who abroad has ever heard of Saint-Denis, to say nothing of Liberty Street?). One sentence in the second paragraph was especially hard to translate: “l’Ouest nous a peut-être fait un enfant dans le dos.” Faire un enfant dans le dos can mean “take advantage of” but also has a more specific sense of getting pregnant against the wishes of one’s partner. Noudelmann explained to me that the idea is that the United States has given birth to French thought without France wanting it to, which is a rather striking sexualization of intellectual traffic, and one that reverses the usual “France is to the USA as feminine is to masculine” imagery.

There’s something curious about this text for an American reader too: doesn’t this tale of Paris-8 as the origin of French Theory run counter to the simplistic ways that French Theory is typically recontextualized in the United States? As far as I can recall from my undergraduate education, we weren’t taught to think of French post-structuralists as coming from a precise institutional location in France; rather, they were contextless ideas that seemed to come from “France” in the abstract, subliminally playing on the high-status connotations that French culture and language still enjoys in the American cultural imagination. There are in fact famous American academics who visit Paris-8, but I think most Americans of my acquaintance who read “theory” have never heard of it.

Well, my American readers, now you have.