These are the books I got from George Stocking‘s office when he decided to give away his book collection in December. They are a strange memorial to the ending of a scholarly career.

critical anthropology of academic culture

These are the books I got from George Stocking‘s office when he decided to give away his book collection in December. They are a strange memorial to the ending of a scholarly career.

this is the university’s skin. at the university of illinois-chicago. some building on the south side of roosevelt road. the branches creeping up across the brick and flung in the sun while the wall is in shadow, the brick stained and blurred and colored, the brick covered by creeping vines, the vines dripping down as if the blood of the bricks were pouring out through the mortar, the snow settled into the vines like cowbirds nesting in places they didn’t build.

Stanley Fish argues directly against an instrumentalist view of higher education:

I have argued that higher education, properly understood, is distinguished by the absence of a direct and designed relationship between its activities and measurable effects in the world.

This is a very old idea that has received periodic re-formulations. Here is a statement by the philosopher Michael Oakeshott that may stand as a representative example: “There is an important difference between learning which is concerned with the degree of understanding necessary to practice a skill, and learning which is expressly focused upon an enterprise of understanding and explaining.”

Understanding and explaining what? The answer is understanding and explaining anything as long as the exercise is not performed with the purpose of intervening in the social and political crises of the moment, as long, that is, as the activity is not regarded as instrumental – valued for its contribution to something more important than itself.

This seems to me not very well phrased, because the distinction between an institutional ideal (which is really what this is about) and institutional reality is not well established; and “instrumentalism” is very clumsily formulated. Fish mentalistically defines being “instrumental” as a matter of purpose or intention; while of course not everything that’s intended to be “useful” actually ends up being useful, and purposes are not often as monolithic as Fish makes them out to be. Is my intrinsic enjoyment of a bag of potato chips, to take the most laughable example, diminished or even altered by the fact that eating is also instrumentally useful for avoiding weakness and eventual death by starvation? Not really; contra Fish, something can be instrinsically valuable while also being useful for some other end, even when that “other end” is, abstractly, far more important than the immediately valuable experience of, say, chewing up crisp little ovals of grease and salt. Purposes can be multiple with regard to a given activity, whose “intrinsic” merits, moreover, aren’t automatically distorted by an instrumental attitude projected onto it. Extrinsic and intrinsic value, instrumentalism vs value en soi, are not mutually exclusive. And Fish is wrong to imagine that scholastic “understanding and explaining” are automatically distorted the minute that someone starts having an intention of “intervening in social crises,” or that the academic merits of academic knowledge are incompatible with their having some other function, like job training.

Faced with demands for higher education to be “relevant” or “engaged,” either by producing a better corporate workforce as business leaders might want, or by teaching social justice as progressive activists would prefer — faced with these demands, anyway, Fish retreats into the argument that “higher education has no use; it is just intrinsically valuable.” It strikes me that this is actually an strangely deceptive move, because as a professor, higher education is obviously, trivially useful: Fish stands to gain an obvious utility — in fact a paycheck! — from the higher education that he argues is a “determined inutility.” Here is the unspoken reality of Fish’s argument: academic knowledge is useless to everyone except those faculty who are paid to reproduce it.

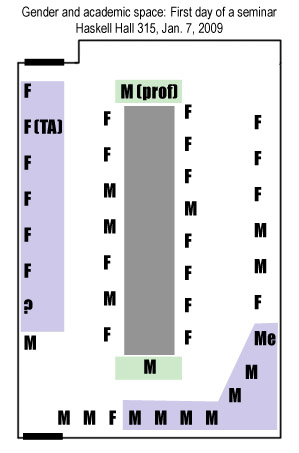

Here is a diagram of how students arranged themselves around the room, on the first day of a seminar that happened to be on space and place. It reveals an obviously gendered system of spontaneous spatial organization.

This is going to be crude and quantitative, but I want to give a bit of concrete evidence bearing on a trend that, I suppose, must already be subjectively apparent to everyone who pays attention to gender in academic life: the tendency for males to speak first, or in particular, to be the first to volunteer comments in large public discussions. This obviously isn’t the case always and everywhere, and must be shaped by a large number of variables: group size, topic, distribution of interest and topical expertise, social rank and authority, and degree of acquaintanceship or shared social belonging, to name a few. For instance, I don’t notice this trend when the anthropology faculty, who are colleagues well known to each other, are responding to guest speakers at the weekly department seminar. But I did notice this trend very strongly at a public lecture by Bernie Sanders in December, where about the first ten speakers were all male, while only a very few women got to comment at all, and they were towards the very end of the line.

But to avoid making claims based purely on the hazardous results of personal experience, let me report the following.

Department Head

“His kingdom isn’t large, but still

He rules it with a royal will

And, as his colleagues sometimes moan,

Needs but a scepter and a throne.

Part teacher only, he’s between

A full professor and a dean.

More like a congressman, by rights,

He represents his field and fights

For added space and extra books,

More office space and shelves and hooks.

He counts his majors, keenly knowing

He has to make a stronger showing

Or (how his loyal heart is torn)

His budget will be sadly shorn.

Above his colleagues quite a distance,

He has a phone and two assistants

And teaches what he wants and when

And takes a day off now and then.

The students all are scared to death,

The new instructor holds his breath,

The others envy, hate, admire,

And try to guess when he’ll retire.”

-Richard Armour, 1956, College English 17(8):450. (There are other examples of this doggerel out there too.)

Let me just note that it’s interesting that the three themes of this poem are: the structure of departmental power (somewhere between monarchy and legislative bargaining); the budget and material supplies (down to the shelves and hooks); and the chair’s affective relations with colleagues and students (envy, fear, suspense, admiration…).

Last month I read in the New York Times that, as the costs of college rise and rise again, “college may become unaffordable for most in U.S.” That struck me as a wretched situation.

It’s probably also false. What’s actually happening, according to another article a few weeks later, is that applications to expensive private universities are dropping, while more students are probably going to go to cheaper schools, particularly public schools. But the question remains: if fewer people got to go to college, why would that be a bad thing? Or rather, what makes higher education valuable?

I have to say I’m skeptical about most of the arguments I’ve encountered in this arena. I have an intuition that there is something worth defending, but most of the existing arguments seem deeply flawed. Here I just want to outline some critical and methodological theses that seem to demand our attention.

At sunrise, even the droll ornamental lakes of the university acquire a certain glimmer. The pond weeds become shadows. The shadows wash over the shores of the lake and hide them, which is much for the better, as this lake is populated by geese who have draped the banks with their droppings, each one about the size of a skinned baby carrot. They number in the thousands. Consequently, the mirrored sheen of this fake pond offers only a very incomplete simulation of a beautiful natural scene.

The skyline of a campus is different when it’s obscured by the trudging stalks of its scrub plants.

The university can so easily be made to become a tipsy line drawing mauled by the shadows of leaves and stalks.

The University of Chicago decorates the tops of its buildings with crosses. They are mostly lost from view, unless you climb to the top of the towers and look out over the rooftops to see them, crosses silhouetted against the sky.

it’s summer in this picture. i was on top of a hill when i took this. i was 18. just before i left for college. the year 2000.

the rows of graves run down the hill to the high brick buildings. the silver dome of the basketball stadium rises like a silly saucer. the trees were the dark green of summer. it was probably hot out.

it’s a little eerie that the view of the university leads down out of a hill of graves. this is the university of connecticut; they have the same thing at cornell university too. a campus graveyard. just a place for the bodies to go when they’re done working, i guess. a convenience, just like the campus coffeeshop. why leave campus when all the amenities are close at hand?

If the campus has a certain relationship with the land, does it also have a relationship to the sky? Does academic space have an upper boundary or a top? Or does it stretch up into the academo-stratosphere (as my friend Jess Falcone puts it) or eventually out into the void where academic “stars” shine?

One of the ways universities organize their peaks is with built objects that rise higher than others, that rise for the sake of rising, because height is symbolically potent: a church, a gilded library cupola, a smokestack, a triplet of water towers, a triplet of flagpoles.

Still not very happy with thinking about the edges of campus either as abject or as sublime, as I discussed the other day. Took some photographs to examine more closely, again of UConn, just past dawn, the day before Thanksgiving.

At the University of Connecticut last week, in Storrs, I observed semantic growth of morbid proportions.

Continue reading “Semantic inflation in campus building names”

How do we understand the politics of the university, again?

Consider the following case. A few years ago there were efforts to get the University of Chicago to divest from Darfur. They failed. At the time, the president Zimmer justified the decision by referring to the Kalven Report, a 1967 document explaining that, in short, the university should be the forum for individuals to formulate their own political positions, but should not itself take political positions. Importantly, there were multiple arguments for what the authors called a “heavy presumption against the university taking collective action or expressing opinions on the political and social issues of the day, or modifying its corporate activities to foster social or political values, however compelling and appealing they may be.” The Kalven Report justifies its conclusions with three arguments:

Continue reading “Kalven report and Chicago academic politics”

I came across a very interesting interview with one Michael Denning, a marxist cultural studies person at Yale. I’m particularly interested in his comments on graduate education; evidently he has organized a research collective co-organized with students. He says there’s a big difference between a seminar, where the teacher doesn’t write but only grades the students’ work, and a collective where everyone is working together. He comments:

“Particularly after the first year, people in a graduate program are part of the profession, they’re part of the industry. They have exactly the same day-to-day concerns as I do: how do you manage teaching on the one hand, and getting your research done on the other, which is the central structure of the research university. That’s why I don’t really think of this as graduate training.”

Continue reading “student-teacher equality & the limits of radical pedagogy”

I notice I seldom post on this blog. I think that rather than trying to make it a commentary on the current academic news, a vast and unrewarding project, I want to spend more time talking about the research literature I’ve encountered on the university. Today I just stumbled across Kate Eichhorn’s “Breach of Copy/rights: The university copy district as abject zone,” in Public Culture 18:3. She comments that universities are typically surrounded by districts of copy shops, which serve as symbolic boundaries for campus, “abject zones” that are necessary but officially repugnant, since they are full of illegal activity – by which she means the unauthorized xeroxing that is rampant in academic life.

I’ve been reading a lot of French sociology of philosophy, and it continues to frustrate me that the major American text in this genre, Randall Collins’ The sociology of philosophies (1998), basically makes no reference to this literature. Admittedly, the French subfield I’ve examined is relatively limited in scope, basically amounting to a very elaborate exploration of the French philosophical field, which is construed in generally orthodox Bourdieuian terms. There’s a lot of stuff about publishing markets, access to jobs, different forms of symbolic capital. But as far as I can tell, the whole French enterprise is dramatically more empirically involved than Collins’ over-ambitious project to theorize all of philosophy throughout world history. (Mostly this involves drawing little network diagrams of who knew whom.)

Continue reading “On french sociology of philosophy”

Timothy Burke predicts the end of university growth in the U.S. for the foreseeable future. He says that colleges will no longer be able to keep raising tuition at such high rates; that endowments will get much lower rates of return (or possibly shrink outright); that fundraising will be harder; and public funds will be scarce.

That gloomy future is perhaps already arriving at even the wealthiest universities. Alison Sider’s article this week at the Maroon, the University of Chicago’s newspaper, indicates that “the University informed nearly 3,000 graduate students that it had lost its major lending partner and could no longer offer student loans.” According to administrators, “most students remained relatively unaffected by the change,” but nonetheless, “international applicants often lack the credit references necessary to obtain loans from increasingly wary banks.”

Not to mention that international students are often more precarious because they can’t legally work off campus. As usual, economic problems hit hardest on the more financially vulnerable.

If one reads Thorstein Veblen’s The Higher Learning In America: A memorandum on the conduct of universities by business men, it only takes a page or two for him to turn to the technological determinants of knowledge. In a scathing passage, he comments:

The modern technology is of an impersonal, matter-of-fact character in an unexampled degree, and the accountancy of modern business management is also of an extremely dispassionate and impartially exacting nature. It results that the modern learning is of a similarly matter-of-fact, mechanistic complexion, and that it similarly leans on statistically dispassionate tests and formulations. Whereas it may fairly be said that the personal equation once — in the days of scholastic learning — was the central and decisive factor in the systematization of knowledge, it is equally fair to say that in later time no effort is spared to eliminate all bias of personality from the technique or the results of science or scholarship. It is the “dry light of science” that is always in request, and great pains is taken to exclude all color of sentimentality.

Yet this highly sterilized, germ-proof system of knowledge, kept in a cool, dry place, commands the affection of modern civilized mankind no less unconditionally, with no more afterthought of an extraneous sanction, than once did the highly personalized mythological and philosophical constructions and interpretations that had the vogue in the days of the schoolmen.

The academic press is particularly provocative these days. In a fascinating Chronicle column by Georgetown’s James O’Donnell, What a Provost Knows, we are informed that, as provost, he alone knows all the secrets of campus finances, the scale of comparative worth embedded in the salary hierarchy, and the general health of the institution. He ends by saying:

“That’s the burden of the job: knowing all the things that others don’t know or would rather not know. Much that I know I can’t talk about, and I have had to get used to being the object of (usually) undeserved suspicion. Because I know so much, my actions are not fully intelligible to those who observe them. The hardest part of being provost has been learning that it’s right and proper that I be suspected — that such vigilance is part of what keeps our institution healthy.

In the end, the burden of knowledge is worth it. The pleasures of the job are many, not least of which is understanding this marvelous institution so well — a Rube Goldberg creation that really does work, and very well indeed. And the opportunity to kibitz on the intellectual lives of more than 500 keenly intelligent and resourceful faculty members is an immense privilege. Even cleaning up their messes and fixing their leaky roofs gives me great satisfaction.”

Three recent articles in the Chronicle of Higher Ed deal with the politics of literary theory and the importation of French post-structuralist thought into the U.S. Jeffrey Williams, in “Why Today’s Publishing World is Reprising the Past,” examines a recent trend towards reprinting famous classics of yesterday’s theory scene — Fredric Jameson, Jonathan Culler, Gayatri Spivak, and the like. “The era of theory was presentist, its stance forward-looking. Now it seems to have shifted to memorializing its own past,” he comments. He explains this partly as the shift from “revolutionary,” unsettled science to the successful institution of a new “theory” paradigm, partly as a result of decreased financial support and increasingly precarious jobs in the humanities. But what seems interesting to me is the shift in temporal orientation itself. Academics play with time in so many ways. Sometimes memorializing the past becomes a strategy for making intellectual progress in the present. Other times, the fantasy of a radical break with the past is the occasion for reproducing the past without knowing it.

Continue reading “New temporalities and spatialities of “theory” in the humanities”