Last weekend there was a march in support of immigrants and against the expulsions of the Roma from France. The march was called “In the face of xenophobia and the politics of pillory: liberty, equality, fraternity,” and was a commentary on increasingly harsh French policing of immigrants this summer. My friend Moacir, who came to the march with me as an honorary participant-observer, has some interesting comments on the mechanical reproduction of its political messages, i.e. on how most people carried pre-typed, printed political signs and how this doesn’t necessarily discredit them, but rather constitutes a show of unity.

It strikes me, in hindsight, that it’s worth emphasizing that the march bore a diversity of political messages. While an anti-Sarkozy, pro-immigrant message was certainly the predominant message and the one picked up by the media, there were also, for instance, a number of people marching on behalf of higher education and research, attempting to add their own message to the mix and to show political solidarity with the larger project.

To the left was the “Recherche Publique Enseignement Supérieur” (Public Research Higher Education) balloon.

Later on, I found the banner of Sauvons l’Université (“Save the University!”). I asked someone what the political situation was in the universities this fall. “It’s the rentrée [ie, homecoming, the start of the year],” I was told, “so there is no situation yet; it remains to be created.” I rather like that tiny comment as a fragment of local political temporality.

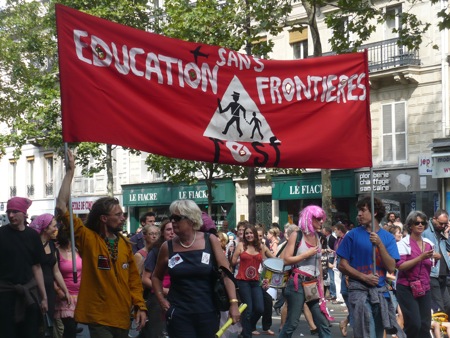

A group I hadn’t heard of: “Education without borders.”

And another one, the Teaching League, who apparently are there to defend secular public education. I asked one of them: haven’t you guys already won? France has had secular education for a century, I’m thinking to myself… Yes, in general, but there’s always something that needs defending, they answered.

This one is even harder to read, but it says: “Let them grow up here” (laissez-les grandir ici). It seems to me based on a very common immigrants’ rights slogan: “We live here, we work here, we’re staying here” (on vit ici, on bosse ici, on reste ici). The strong, poetically repetitive emphasis on being here, a case of what linguists would call spatial deixis, is a key component of this political symbolism. At the same time, there’s a complex invocation of political temporality here too. To begin with, there’s the temporality of exhortation, the temporality of a political demand (let them!…). But at the same time, this sign invokes the whole temporality of living, of growing up, of children in a crowd holding hands, of children being allowed to stay where they are, allowed to eventually become full-fledged French citizens and to fulfill their role in reproducing French society.

What’s poignant about this sign, and what makes it different from the slogan “we live here, we work here, we’re staying here,” is that it’s not the children themselves who are holding it; it’s the adults who are demanding a future on their behalf. At the same time, rather less poignantly, it’s the native-born white French here who are demanding a sort of mercy for immigrants. There’s a whole dimension of concealed group membership in a slogan like this one, a “them” contrasted to a tacit “us.” Most French street politics seem to be mainly about “us” and to involve groups advocating on behalf of themselves, but immigrants rights politics has an unusual orientation towards defending the other, defending the out-group. “Don’t touch my friend” (touche pas à mon pote) is a super common slogan in these contexts, and it has the same rhetorical structure as this sign: an appeal to power on behalf of some powerless third party.

And, of course, it also draws on the imagery of schoolchildrens’ crosswalk signs. Or perhaps those children holding hands are an image of the next generation of street protesters?

Related to the temporal frame of political fragility that I heard evoked by Sauvons l’Université, these people’s t-shirts read: “provisionally at liberty.” As if invoking the spectre of a future in which the government will round them up.

The same temporal frame of a fragile and hazardous future comes up in this handmade sign: “Tomorrow it could be you!!” As Moacir’s post notes, the memory of the deportation of the Jews was quite present in this event, and I have an intuition that this slogan here also has a bit of an echo of that famous poem about “first they came for the communists…”

Sarkozy’s government has for some time declined all interest in street protests, but it’s interesting to note that lately, especially with this week’s much larger march against their reforms of the pension system, they seem to be at least pretending to pay a bit of attention to this form of political expression.

2 thoughts on “Higher education marches against xenophobia”

Comments are closed.