I just got home from a great panel on “Re-Creating Universities Through Critical Ethnography” at the Society for Cultural Anthropology Meetings. It was organized by Davydd Greenwood, who was my teacher in college and has been working on anthropology of higher education for longer than I’ve been an academic. We also had Susan Wright, who’s worked on European higher education reforms since the 1990s, and Wes Shumar, who became a prominent critic of commodified higher education with College for Sale.

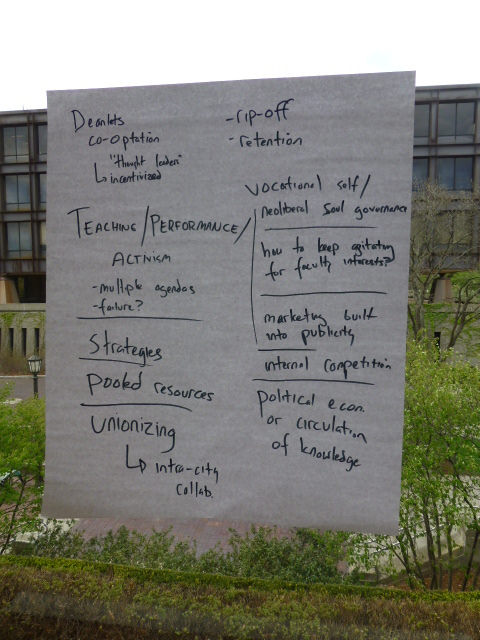

Davydd is known best for doing participatory action research, so naturally we wanted to devote half of the panel time to working collaboratively with the audience. We planned to ask them questions like these:

- How do we bring about change in the university when so many of us are deeply committed to the hierarchies and the elitism in the current systems of higher education? (Especially as neoliberalism pressures us to be more individualistic and more competitive.)

- Let’s be utopian: What kind of higher education do we truly want, and how might we get there from here?

- Which anthropological concepts/ethnographic texts are useful for analyzing our own practices and devising ways to change them?

- How does the university work when the current management and accountability models, if fully applied, would actually destroy them?

We were also hoping that, after sharing our presentations with the audience, we could engage them in trying to collectively generate new questions, new research agendas, and new strategies for re-creating universities. That didn’t entirely work out. What happened instead was experience-sharing – the crowd was small enough that everyone could take a turn at describing their own institutional circumstances and dilemmas. This turned up a wide range of situations, everyone from graduate student unionizers and undergraduates to junior and senior faculty. Correspondingly, the participants shared a wide range of strategies for intervening in their institutions: everything from open-source publishing advocacy to arguing over budgets to militant faculty committee politics. (I did notice, incidentally, that graduate students were under-represented in the audience compared to the conference public in general; I’m not quite sure why.)

But I was left wondering more than ever about the risks of specialization in anthropological work on universities. We — the panelists — were there in a double role: as facilitators of collaboration, but also as experts on the panel topic. I came away feeling that these two roles were more in conflict than one might hope. One might even say, abstractly, that the usual logic of expertise is at odds with the logic of collaboration – “expertise” seems to name a vertical relationship (the most knowledgeable people are privileged) while collaboration hopes to be more horizontal (everyone brings something to the table). Of course, this doesn’t have to be a problem in practice; there are ways of using expertise more collaboratively, less hierarchically. Still, I came away from our panel thinking that we were overly optimistic in asking our audience to instantly talk like higher education researchers, suggesting new research agendas. We said we were hoping for collaboration, but I think we may have wanted something more. Perhaps we had hoped that they would act as our peers.

There’s a logistical element here that’s worth noting. Collaboration, as Davydd reminded me, takes a large investment of time and energy, and it was probably unrealistic to expect a new form of interaction to emerge in the space of 90 minutes. The traditional logic of expertise, by contrast, is a script that academics are automatically trained to practice. In a traditional conference panel, you don’t need to spend time figuring out how to interact, because you come in with a set of expectations and habits that presuppose you to participate in the usual logic of deferring to expert knowledge. It’s efficient not to challenge these habits.

In the context of doing critical research on university institutions, this is worrisome. Surely the point of a critical anthropology of universities is to help improve these institutions by working broadly with their denizens. In that context, it would be a terrible irony if we ended up producing narrow expert knowledge in the usual disciplinary mode. (Or at least, if this were mainly what we produced.)

There is a lot of precedent in higher education for “critical” fields like feminism being defanged by walling them off into their own disciplinary space. Is this inevitable for “critical university studies” as well? The recent invention of the “critical university studies” label seems to point in that direction.

If we’re not to end up there, I think we may need to work harder at figuring out how to interrupt the usual logics of expertise even when they help bring attention to our work.

I actually did not expect fulsome participation in the second half of our panel based on decades of experience with participatory processes. Action research and other participatory techniques necessarily involve a series of steps, often represented as a spiral of sharing information and experiences, collaborative reflections, action designs, action, analysis of the results and new information sharing, etc. Precisely because neo-Taylorism shuts down sharing information and experiences as a control strategy, when you first open an arena for sharing, what normally happens is process of recounting experiences and locating the speaker in the scene. This is why action research search conferences begin with hours spent on building a shared history before moving to thoughts about the present, the future, and then to the analysis of collaborative actions.

So the first step is creating a space for sharing experiences and, in highly repressive situations, this phase often takes a while. People who have been silenced often require time to develop their own story and to figure out how to tell it, to say nothing of deciding if the space is safe enough to do so. For major organizational change processes, these processes need eventually to include the other key stakeholder groups, in our case, students from across the institution with diverse backgrounds and experiences, administrative staff members across the major functions, etc. Whether or not senior administration is included is a contextual decision. With oppressive administrations, it is not smart to do so because figuring out actions to deal with them and their supporters is likely to emerge as a key issue. Also most stakeholders will not feel “safe” in their presence and will be silenced or will self censor. When the rest of the stakeholders are ready, these “uppers” are either invited into the process or become the targets of the other stakeholders change projects.

We had one (though diverse) stakeholder group present and the discussion went as far as it could under the circumstances of being a panel at a professional, disciplinary meeting. My reaction was that the discussion was not only franker than I expected but that the voices of the younger generation present embodied many of the experiences we recounted in our presentations. That our presentations resonated was confirming to me. That members of the audience stayed suggested there is energy for change when the context permits. It is a long road ahead. This is why the book Morten Levin and I are copyediting links Bildung, academic integrity and freedom, change away from neo-Taylorism and neoliberalism, and the link between the changes needed, action research, and promoting participatory democracy more broadly.

It is no accident that films like the “Hunger Games” and the dystopias of current video games resonate with so many people. Kafka also lives at “Wannabe U”.

Hello Eli and Davydd. I was unable to attend the conference/session and discussion, so am glad to read these commentaries. I’m not surprised that there were few graduate students, as–unless things have changed a lot since I was at Cornell–many would be hesitant to critique the institution(s) they want to be employed by, or hesitant to risk being seen as “not one of us” (or in the UK, “N. U”) in a career dominated by people with high degrees of class privilege–such as you’d find at SCA meetings–who have much at stake in keeping universities running along lines that ulitmately serve them.

Yes, that’s a big generalization, but I’ve seen something of how class interests play out in the small university I’ve worked at for the past 20 years, one with no endowment, many first generation university students, many from rural backgrounds, and many meeting the minimum entrance requirements. Yet their teachers are mostly from elite institutions (outside Canada), or are the descendents of regional elites.

Like others in the conference discussion session, I’m situating myself and my own story, and what a great place to start as so many relevant parts of the story of players are often–by class consensus/norms–left unsaid. And that’s where our insights often come from.

Shumar’s apt suggestion that we confront and consider the selves we have become in institutions is fascinating, but how many–other than those coming to such a panel–would want to publicly do that and act on it? We might also ask how the selves we are raised to be fits us, or makes us ill at ease in, or not inclinded to truly question the institutions we find ourselves working in.

Davydd: your describing university as part theme park is wonderful. Trent–where I teach–has slogans such as “where the world learns together, ” and “come to Trent and see the world”. Compared to other Ontario universities, there are relatively few non-white/International students. Yet it’s marketed explicitly as a place to study where you can meet students from other countries. I know some non-Canadian students have said they read those slogans and feel like “an attraction” , especially after discovering their collective minority status in a sea of pale faces.

Although (as Shumar says) univerisities may ignore racial and gender violence, in general they promote the idea (at least) of racial and gender diversity, as a step to democratizing education. What has yet to be accepted is that social class shapes the culture of universities as much as gender or race, and –in my view–speaking of gender or race is the safer option these days and gives the impression that one can speak “in a different voice”, and the impression that those different voices are tolerated and even welcomed. Having differently gendered and coloured bodies on campus gives the appearance of diversity, while social class un-diversity goes unseen. The poor(er) are not always a “visible minority” after all. The children of the poor come to elite institutions (either through real sacrifice on the part of parents, or through scholarships) and learn to “pass” (academically, and socially), and be be “professional” as they learn the culture of elite classes. At the same time the children of the elite learn by “seeing the world” in those classmates who are different, and in diverse curriculum (theme park?) that tells about them, a new kind of basis of privilege: the ability to be at ease in a wide varity of contexts –to create the image of intimacy or acceptance–without actually accepting those others as your peers.

Khan describes this sort of process in his study of priviledge in private high school education (“Privilege….” Princeton UP, 2011), and argues that these attempts at democratizing education in fact have the effect of reproducing social hierarchies while disquising that process of reproduction.

In short, helping lower class/poorer students get into university is one thing. But it seems that the on the ground socialization of these students (given the class structure/norms of universities) mitigates against the possibility of them (and us) developing into the kind of participants, the kind of “selves we have become” who can question what universities are today. Instead, promoting diversity of race/gender (as a kind of, or part of theme park) can help mask and facilitate the maintanence of universities, of all kinds, as institutions tied with very particular kinds of interests.

Thanks so much for the great commentary, Sharon!

I completely agree with your observations about the ways that hierarchy interferes with any kind of institutional critique. My experience, having gotten my Ph.D. in 2014, is that almost all previously activist graduate students abandon all political involvement when they are looking for jobs. It’s understandable but also a telling commentary on institutional intimidation.

As far as the social class angle, I also think this is completely true at middle-class and elite universities — my sense, though, is that the story about class would be completely different at a very working-class institution (especially the 2-year places). Where I teach right now at Whittier College, there is a lot of class diversity alongside ethnic diversity, which the faculty talks about quite a lot, to their credit, though I’m not sure exactly how students think about it. I would tentatively observe that the massive social diversity seems to *decrease* identity politics thinking among students, perhaps because Latino/a students are a majority of the student body.