Earlier this fall I wrote to someone I’d met at Paris-8, a professor, to ask if we could meet and talk about campus politics. “Actually I just dropped out,” he said. (By which he meant “retired,” though it was in difficult institutional circumstances.) “But you’re welcome to come visit me in Brittany,” he added. Not that many French academics have invited me to their homes, so I was happy to accept, and last weekend I managed to get there in spite of the nationwide rail strikes.

Here I just want to show you a little of what the house looked like.

Seen from the quiet back street where it sat, the house looked conventional enough, with a solid stone façade, high windows with the obligatory shutters, a witch’s hat of a gable.

If we look in through the garden gate, though, we can see that the garden is decidedly non-Cartesian, the path is narrow, the entrance bowed over with branches. The garden is a protected space, walled off, the plants preserving the boundaries of private life.

If we go farther into the garden (these next few pictures were from the next day, which was cloudy) we see that the space doesn’t open up into a large open lawn, but rather is divided into little areas with different things, the bush that shelters the bicycle trailer, the path that’s edged by a long clothesline, a brushpile higher than your head.

At the very back of the yard, a workshop was under construction. Building materials and tools piled everywhere. On the windowsill of the unfinished building was a curious row of wooden shoes, and inside there was a bass drum waiting to be played.

The yard was patrolled by a cat.

If we go back towards the street, we can see the dramatic difference between the front and back sides of the house. The front was decorated with a façade and full of windows. The back side was largely windowless and bare, the staircase being set against the blank wall at left. The main entrance to the house was unused, and the kitchen entrance through that glass porch became the main entry.

The little motorbike used for errands is just visible at left, its round mirrors like insect eyes.

From inside the house, we can look back out through the kitchen door, the long rows of pots and pans barely visible in the reflected daylight.

In our first real look at the kitchen, we immediately see what to me was the most fascinating phenomenon in this house: the incredible density and diversity of physical objects. Every horizontal surface is occupied. There are pots and pans of all types and styles. There are ladles and clothespins over the stove, an intestinal string of dangling garlic, a silver cylinder of an electric kettle. Bottled water in a plastic can with a handle, crowds of orange-tipped spices parading on the shelf, various kinds of pottery that I don’t have the vocabulary to classify. Dishes waiting to be washed, dishes waiting to be used. Beans in a jar, a bottle of Pepsi, a mortar used for grinding up grain. It was a space of managed chaos.

Facing the street was a big room that served for eating, for storing, for collecting objects, for sitting in armchairs. It was a room that had an even more astounding diversity of objects: objects of culture, of art (in unclassifiably many styles), of music (a piano and a radio), of business (on a desk with papers), of children (a toy train). Let me show you some of the things that were to be found in the corners of this room.

The table under the window had metal tools, a bowl full of collected rocks, a small watering can, a small lamp, a roll of twine, a black shovel, a tiny model lighthouse in checkered black and white, a big hollow tube of a black candle melted to a round stone that served as its base.

On the other side of the dining table, an immense sideboard held little art objects, family photos, tiny dolls, animals in plastic, a kid’s drawing, a watch, some empty bottles, a thermometer, a feather, a little clock, a folded bandanna, a silver pail, a toy rooster, beads, an antelope figure, a little green tree, a lavender rock…

I agreed with my host that my glass of juice on the dining table was beautiful in the light.

The other end of the room was equally complicated to look at. Mix of antique furniture with a scattering of mundane things, an ornate mirror beside a child’s blue globe, a carved cabinet beside a cardboard box, a fancy brimmed hat beside a mass-produced red backpack. This scene, like the others, was not particularly arranged to be seen; it was more like the accidental result of a rising tide of inherited and found objects, overflowing in every corner.

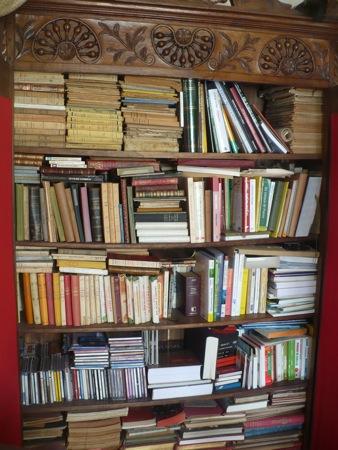

There was a huge armoire full of books. All sorts. Plant guides, French-German dictionary, a submarine guide to the Atlantic coast, novels by French writers I’ve never heard of, Michel Foucault’s Les Mots et les Choses, bird guides, old books whose pages needed to be cut apart with a knife if you were going to read them.

If we climb up the stairs to the landing on the first floor (which Americans would call the second floor; but French floor numbering starts at 0), we come to a pair of mirrors and a table with a new assortment of art objects and a little clock. I decided to leave myself in the picture for once. Wouldn’t want to be one of those ethnographers who effaces themselves from their representations of the field.

Around the corner, we find a bathroom that used to be a bedroom. This wasn’t the kind of house that originally had a shower, I gather, so half of one of the bedrooms had been converted for the purpose. It made for an odd kind of mixed-used space; this half of the room looks like a bathroom, while the other half (off to the right) was a bedroom with fluffy comforter, as if the room were a page from the children’s book Magical Changes where you recombine different images in surreal fashion.

If we climb the stairs to the third floor, the walls get a bit less decorated and it feels a bit more spacious. There was a skylight that seemed more modern than the traditional French windows on the lower floors.

Finally at the top of the house was a long high-ceilinged bedroom where I stayed up under the eaves. A narrow window peeked out under the gable I showed in the first picture above. It looked old, its paint a bit flaked, partly cracked, the shutter trimmed with rust.

Out the window was a view of the town, the pike of the cathedral about to spear the cloud in the distance.

Arabic or Turkish art objects off in the corner, more stored than looked at, but nonetheless making you feel like you had suddenly fallen into a glimpse of a completely non-French world.

Over the low mattress where I slept loomed a little constellation of lamps on the dresser. (I see I hadn’t made the bed.)

I won’t give much of an analysis of this scene for now, since I have other things to write today, but I find it interesting to ponder the domestic history apparent in this thicket of objects. The house was in its third generation in the family, presumably accumulating stuff all the while; probably most of the things there had little histories of their own. I’m not sure that I would even know how to classify all the objects in these photos; it would be impossible to find a neat distinction here, for instance, between “useful” and “aesthetic” objects. Even some of the most utilitarian kitchen objects were aestheticized, stylized; while conversely, even something seemingly decorative like a round stone might end up serving as an impromptu candelabra. I was reminded again that there’s way more to someone’s life than the little fragment of a self that gets presented on a university campus. A professor’s life — or at least this one — has a long history of social relationships that leave little traces of themselves in the form of collected things in the home. And this history (from what I heard of it) no more adds up to a single linear narrative than the mass of things in the living room conformed to a single principle of accumulation.

My host, I have to say, was someone who reminded me enormously of old American hippies of my acquaintance, the kind of person who you’d find at Paris-8 far more often than at more traditional French universities. He seemed to have a strong sense that his house was a non-normative space, a place that needed “cleaning up” to be presentable to company; and indeed, his home was noticeably more cluttered than other faculty homes I’ve glimpsed. At the same time, it was a tremendously lively space, full of projects done and half-done; most faculty don’t build their own workshops in the back of the garden, and that wasn’t even his only construction project. We can see here, it seems to me, that the home can be a space of deep non-normativity, partially liberated from the judgmental attitudes of the neighbors or the public, a space where an alternative order can be created that diverges from French society’s usual obligations of neatness and propriety.

There’s a lesson here for researchers, like me, whose main ethnographic sites are institutional ones. If you only look at what happens in, say, a campus, you’re at risk of forgetting that what you’re looking at is one of the most highly regimented spaces in the society in question, and probably needs to be understood in relationship to the relative spaces of freedom that people have in their domestic life. No one lives their whole life in institutional space, after all. At the same time, on the other hand, a foreigner like me is bound to have limited access to these domestic spaces, especially when they’re not the main focus of the project.

Maybe in some future project I can look into the interface between domestic and professional life in academia. I imagine that for many faculty, this boundary zone is full of painful compromise and fracture, somewhat like a dislocated shoulder.

some people do live their whole lives in institutional spaces– but not in the particular institutions that are universities. related to the study of the interface between domestic and professional life, you could also think about the ways people create meaning or express themselves with the objects in their offices (if they’re allotted office space).

hey cait, nice to hear from you! yes, you’re right that there are people who live in prisons, asylums, army barracks, refugee camps, and so on. it’s worth noting, still, that even in these seemingly 24/7 total institutions, people don’t usually spend their whole lives there — they usually weren’t born into them, usually aren’t there until they die, etc. so in that respect even total institutions aren’t that total.

another problem with my offhand comment about “institutional spaces” is that, when you come down to it, even seemingly unstructured spaces like “the family” or “the home” are no less institutions than a university, in a more holistic, sociological sense of “social institution.” i guess what i should have invoked in the post was some kind of a distinction between impersonal, bureaucratic, mass institutions (like universities) and the institutions of “private life” like a home… not sure that this distinction is completely solid either, but it’s the first thing that comes to mind. does your social theory class this semester have anything to say about this?

Wow, really interesting commentary. I enjoyed reading it as much as the pictures.

Institutionalized people don’t have such a private space; it’s a bit of a privilege. But your friend seems exceptional.

I guess it’s fitting that a post about a home is the post whose discussion thread is dominated by my own family!

Wonderful post. I think Melissa Gregg’s forthcoming book will speak to the interface you note at the end!

Thanks, Ana, and it’s good to hear from you. I love that your blog is about “solidarities, fetishism, urbanism, nuns, begging, privilege, faith and reading”! I will add it to my list of things to read.

BLUSH.

Hi Eli,

Great house tour…makes me wonder what a comparative tour would look/feel like in the U.S. Or somewhere completely different. Within four square blocks of my professorial home (w/it’s non-normative dirt), there are at least twenty faculty homes…I’ve never thought to stop and count, but I think that’d be accurate. But we don’t interact as faculty in these spaces at all. Very little “sherry and dialogue” going on. More “waving on the way to the kid’s soccer game”. Despite the enclaves created by our “college towns”, we don’t seem to have a sense of intellectual solidarity. Or perhaps it’s because of the college town we have no clear sense of us vs them?

Fascinating.