This is the scholarly lion at columbia university. It cannot roar. It can’t charge. It can’t even move. It is only a statue.

One wonders, frankly, what kind of comment on scholarship is implicit in this puzzling object, with its ruffled main, its gnarled lips, its green face the color of sea-beaten algae or refrigerated mold or weathered bronze, its thick lips, its empty eyes, its stiffened limbs. Are scholars meant to be like lions, brave and heroic, ready to seize the truth in their jaws, to roar at lies, to stand guard before virtue and prestige? Or are scholars here represented as statues, statues of something that might once have been brave when it was alive and lithe, but that now is halted, appropriated and bronzed?

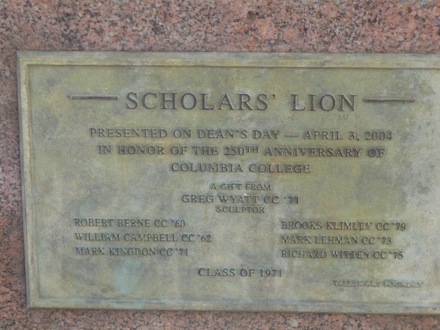

To make matters semiotically worse, the lion here is technically not called “the scholarly lion” but “the scholars’ lion”:

But this datum of course does not offer us any simple interpretations either. We gather that the statue was presented on Dean’s Day, April 3, 2004, in honor of the 250th anniversary of Columbia College. It appears to be a commemorative gift to the University by the class of 1971. So whatever the relation between name and object, the whole assemblage appears to signify the university’s commemorative relation to itself, a token of its high self-regard and a compliment on its longevity. (Why celebrate anniversaries, after all, unless the aging process itself is taken as an accomplishment, longevity taken as a virtue?)

But why should scholars possess a lion? Is it their guardian? Their pet? Their mascot, symbolizing them in a peculiar combination of valor and animality that seems totally contrary to the received image of scholarly activity? Perhaps the scholars’ lion is their symbol because it condenses everything that, ideologically speaking, scholars are not. The lion, a bodily incarnation of public action, seems almost the inverse of the scholar, a spiritually ethereal figure closeted off in the library.

Further investigation only suggests more puzzles. For one thing, this statue seems to have won the award for “best metal testicles” from the Village Voice. And for another, the Columbia Lion, of which this is one incarnation, is said to be the basis for the famous MGM lion that roars at the start of all those films. Who would have thought that that lion had any connection to scholarship?

And – here’s a more traditional anthropological question for you – what does it mean that universities have totem animals? Doesn’t that rather give the lie to the fantasy of universities as quintessentially modern, progressive institutions? What then is the lion telling us about the university’s relation to history and tradition? What is a statue as a commentary on an institution’s place in society?

There’s something contradictory in the way that the Ivy League universities represent their place in history: while claiming to maintain their traditions, their alumni groups, their internal identity in much the same way (they insinuate) it has long existed, they aspire to be places that create the mass future, that reproduce society and the world in new and better ways. As if their internal stasis could correspond to their dynamic effects on their surroundings. Surely no one ever asserts this in so many words, but even if this formula is over-simple, I expect one could document a very unsteady ideological compromise between what’s supposed to be fixed or even past-oriented and what’s supposed to be changing and future-oriented, in these elite universities.