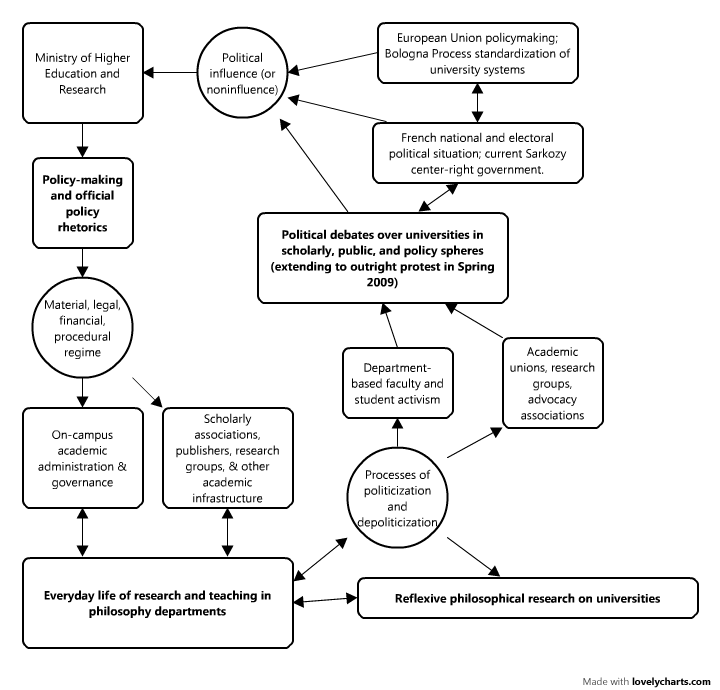

I’ve been working on a grant application for next year and thinking about how to simplify my field situation for the sake of the grant reviewers. I started drawing some diagrams in the process, and while procrastinating from actually writing the text of my grant request, thought I would figure out how to make computer-generated flowcharts of these diagrams. So here’s a diagram – one of many such possible diagrams, of course – of the structure of French university practice and politics:

(Diagram generated with lovely charts. Click through for a larger image.)

The point of this diagram is to show how university politics is connected to everyday life in French universities. You could say that it is a diagram of how students and teachers become or don’t become activists in the university system, and how their activism feeds back into the general political and organizational life of this system. So you have here a diagram of a giant feedback loop. It attempts to capture some of the paths of practical entanglement, influence, action, and organizational interconnection that jointly determine how universities are reformed and how academic lives are lived.

On the left, we have the top-down system of policy-making and distribution of resources by the Ministry of Higher Education (and Research). It starts at the top in the Ministry; this Ministry has a guiding policy direction, with which it puts together a regulatory regime and distributes resources; these regulations and resources then constrain local university administrations and other kinds of scholarly organizations (journals, professional associations, and the like); and in turn these more proximate organizations reshape the everyday worlds of ordinary teaching and research. You have here the classical mode of top-down national university governance — which, in spite of the controversial current efforts to decentralize university administration, remains a marvelously Napoleonic institution in comparison to U.S. higher education.

On the right side of the diagram, I’m trying to represent the processes of politicization (and depoliticization) which flow from everyday life in the universities out into a broader world of political debate. This begins with faculty and students who become politicized; they join scholarly associations or unions, organize events or write texts. Sometimes their organization is local on the scale of the campus and sometimes it’s more centered on translocal or national organizations; at any rate they eventually constitute a sort of political sphere of debate over the universities. At the same time, a few teachers and students decide to do research on the university itself, making their institutional context into their research object; I’m particularly interested in the way this plays out among philosophers (e.g. Alain Renaut or Plinio Prado). Finally, of course, there are lots of ordinary academics who aren’t politicized, who just go about their academic business, who have no use for activism or who have withdrawn from it; these people fall off of this diagram, not playing any direct role in the politics of the university system.

Now, the world of political debate over the universities does feed back into the policy process, but it’s only one influence on the policy-making at the Ministry, and not a particularly dominant influence either. It seems to me that French educational policy is probably more influenced by the Sarkozy government’s overall political priorities, or by general trends in European higher education, than by the clamoring of French editorialists and activists outside the official channels. Which is why the diagram has a node to designate “political influence or noninfluence.”

At the same time, I should note an additional channel of feedback that I’ve left off my diagram: there’s also a channel of official consultation and a system of shared governance that connects everyday academic life back up to the policymakers. There are consulting committees and official reports, there’s the Conseil National des Universités which is involved in disciplinary governance and credentialing, there are in short a lot of ways for mundane university actors to be involved in the governance process without resorting to outright political advocacy. But these official channels play little role in my research, for the time being. Perhaps next year I can add them to my agenda.

I’ve been meaning to give a kind of structural overview of the French university situation. The broader picture of demographics, national university distribution, money, and so on remains to be presented here; but for now, perhaps this image can give a sense of the highly interconnected political system that controls universities in this country.

Note to self: it’s not a diagram that aspires to reveal anything extremely surprising. The point here is to schematize and simplify the common sense functioning of an institutional situation so that the structure of the obvious becomes evident.

Diagrams like this are clarifying. Too often, academia does not reward clarity.

Thanks, Mike. I’m curious: does this diagram seem roughly plausible to you? I mean I know you don’t know the empirical details about French higher ed, but does it seem to you that the diagram is logical? Are there other things you’d want to see added in a future iteration?

I’m also working on a diagram to try and represent the process of classifying and quantifying research ‘outputs’ as a basis for the introduction of differential research funding between universities and within univesities in Denmark. I’m also a novice at this kind of diagram but I’ve found the work of ‘institutional ethnographers’ around Dorothy Smith in Canada extremely helpful. They also try to relate everyday life to institutional structures and what they call ‘ruling relations’. Two things they would add to your diagram are, first, the texts that mediate these relations, either as one-off documents (eg consultative documents) or as new techniques for ordering relations (e.g. new forms of reporting, accounting or evaluation). Second, they include a time line (and when exploring reform processes, there’s an issue about how to represent one-off events and recurrent activities that gradually take on a new shape). They also have a more standardised meaning for squares, circles, thick, dotted lines etc – yours needs a key. I’m struggling to find a good guidebook to their ‘mapping’ techniques in institutional ethnography. The best example of its use in practice that I’ve found so far is Susan Marie Turner ‘Mapping institutions as work and texts’ in Dorthy Smith (ed) 2006 Institutional Ethngraphy as Practice (Rowman and Littlefield).

Thanks, Sue, this is very helpful! I’m not sure that my diagram even has a very consistent key, though the diagramming software that I used suggested that circles were for processes (I’m not even sure now what it said rectangles were for). But in the next iteration I will make sure of that, and I’m eager to look up Turner’s chapter.

Eli, I’ll try to get back to you on this. Also, have you tried http://freemind.sourceforge.net/wiki/index.php/Main_Page ?

hey…i really like your blog and your thesis. i’ve been trying to draw a diagram of sorts of my area of proposed study as well…did you send the diagram to your grant reviewing committee? how did that go?

Hi Eli, I think you’ve captured the general scheme very well and although simple, such a diagram reminds us of the pieces and parts which often get lost. I’m coming to this very late, so I’ll try to catch up in a more recent forum.