Contemporary commentators often give us the sense that the increasing precarity of academic work is a recent and novel phenomenon. As I’ve noted before, in the American case this sometimes seems to rest on the historically inaccurate fantasy of a previous Golden Era of tenure, even though tenure, on further investigation, was apparently a rather recent invention that only became widespread in the post-1945 period, only lasted a few decades, and never covered all academic staff anyway. Don’t get me wrong; I’m not saying that there aren’t ongoing degradations in the conditions of academic work; the last twenty years have not been pretty in terms of US academic employment. Things look particularly grim in Britain this year, given the threats of 80% cuts in public university funding; in spite of the fantasy that tuition will increase to compensate, it’s easy to imagine that many humanities departments will be closed down. (Or already have been.) And as I’ve discussed before, France has seen a growing discourse on academic precarity the last year or two.

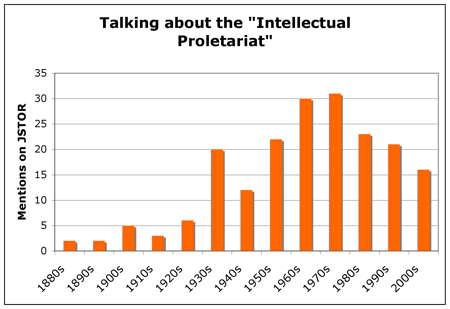

But it may help our sense of historical consciousness to discover that even a hundred years ago, some people already had a fairly clear discourse on precarious intellectual work. I’m not a historian and I can’t pretend to give the whole picture, but if we search on JSTOR for “intellectual proletariat” the first use of the term is as early as 1884, and the term has been used occasionally ever since, being used on average a few times per year in the scholarly literature since the 1930s.

In 1904, one Frances J. Davenport wrote a review in the Journal of Political Economy of a book by Carlo Marin. Marin apparently set out to demonstrate that “the inferiority of the Italian is by no means innate, but is the result of his extreme poverty.” Davenport went on to summarize as follows:

The fundamental cause of the poverty of Italy, according to Dr. Marin, is the faulty system of education. Numerous but poorly equipped universities train great numbers of lawyers and of doctors, who cannot find employment and form an intellectual proletariat. On the other hand, the few schools of agriculture, industry and commerce are scantily attended, and the instruction lacks a practical character. Reduce the number of universities, improve their scientific equipment, and introduce into every university thoroughly practical instruction in agriculture, industry, and commerce; work directly for economic development and social improvement will follow.

It’s worth noting, in passing, that the word “proletariat” itself only came into the English language in the 1840s (according to the OED), so we can infer that it only took a few decades for it to be extended metaphorically to refer to intellectuals as well. At any rate, Davenport’s language sounds eerily similar to contemporary discourses on the impracticality of university education, and it certainly echoes the contemporary desire to make universities more economically useful. I notice that there is nothing directly political about this discourse; while “overeducation” and unemployed elites are sometimes perceived as a political threat, here they are merely characterized as a lost economic opportunity for the nation.

It is, nonetheless, unsurprising that the term “intellectual proletariat” was also used early on by overtly left-wing writers. As early as 1909, the politically complicated American socialist leader Morris Hillquit argued that “intellectual proletarians” formed part of the working class. From his book ‘Socialism in theory and practice‘:

The word Proletarian signifies a workingman who does not own his tools of labor, a wage worker; but in its wider application it embraces the entire propertyless class of workers. Thus we speak not only of the “industrial” proletarian, but also of the “agricultural” proletarian, the farmer who does not own his land, or the hired farm hand; and even of the “intellectual” proletarian, the professional who depends upon an unsteady and uncertain hiring out of his talents for a living.

That sounds like a pretty contemporary description of precarious faculty to me: “the professional who depends on an unsteady and uncertain hiring out of his [or her] talents for a living.” At the time, though, it appears that American faculty at this point weren’t particularly conscious of their status as “intellectual proletarians.” A couple of years earlier, around 1905 (but only published in 1918), Thorstein Veblen had described the labor situation in American universities thus:

There is no trades-union among university teachers, and no collective bargaining. There appears to be a feeling prevalent among them that their salaries are not of the nature of wages, and that there would be a species of moral obliquity implied in overtly so dealing with the matter. And in the individual bargaining by which the rate of pay is determined the directorate may easily be tempted to seek an economical way out, by offering a low rate of pay coupled with a higher academic rank. The plea is always ready to hand that the university is in want of the necessary funds and is constrained to economize where it can. So an advance in nominal rank is made to serve in place of an advance in salary, the former being the less costly commodity for the time being. Indeed, so frequent are such departures from the normal scale as to have given rise to the (no doubt ill-advised) suggestion that this may be one of the chief uses of the adopted schedule of normal salaries. So an employee of the university may not infrequently find himself constrained to accept, as part payment, an expensive increment of dignity attaching to a higher rank than his salary account would indicate. Such an outcome of individual bargaining is all the more likely in the academic community, since there is no settled code of professional ethics governing the conduct of business enterprise in academic management, as contrasted with the traffic of ordinary competitive business.

It seems that this moral norm of being “above” collective bargaining broke down slightly over the next few decades. As Zach has discovered in a great bit of archival research, by the 1930s faculty were thinking about unionization. From a 1931 article in a Minneapolis labor journal:

Forces beyond their control are driving university professors to the status of employees and are forcing them to the point where they must form “a guild or a union,” declared Professor Randall Henderson, president Yale chapter of the American Association of University Professors, in his annual report.

Professor Henderson is shocked at the prospect, but he can see no alternate to cope with the industrialization of universities that are now being ruled from above. He warns the controlling factors of American universities that a guild or a union is inevitable unless there is a reform in methods of administration.

The universities, he said, have become industrialized and are now being operated on the factory system. The old New England type of college government is impossible, he said.

In spite of this early discussion of academic “industrialization,” I am obliged to remark that there is an ongoing conflict, even to this day, about whether American university faculty are “workers” and, if so, what kind of workers they are. I can testify from experience that many elite faculty in the humanities don’t see themselves as “workers,” having instead an artisanal, connoisseurial, artistic or even amateur relationship to their labor. And thanks to the 1980 Yeshiva vs. NLRB decision, private university faculty are classified legally as having managerial status and hence not being eligible for collective bargaining rights. At the same time, of course, academic labor activists continue to claim that “we are workers.” One is tempted to remark that current American debates over academic labor haven’t much evolved, in terms of their framing, over the last 80 years.

But one has to observe, at the same time, that these debates on the intellectual proletariat weren’t limited to the United States. As it turns out, they were also happening in Germany in the 30s. The other day I was reading some (very harsh) comments by Theodor Adorno on Karl Mannheim’s “sociology of knowledge”; Adorno summarizes a book that Mannheim had published in German in 1935, translated into English in 1940, called Man and Society in an Age of Reconstruction. I haven’t read that, but I gather that Mannheim was commenting on the intellectual situation in inter-war Germany (1920s or early 1930s), and Adorno’s gloss on Mannheim’s analysis makes it sound like a very familiar situation.

Mannheim speaks of a “proletarianization of the intelligentsia.” He is correct in calling attention to the fact that the cultural market is flooded; there are, he observes, more culturally qualified (from the standpoint of formal education, that is) people available than there are suitable positions for them. This situation, however, is supposed to lead to a drop in the social value of culture, since it is ”a sociological law that the social value of cultural goods is a function of the social status of those who produce them.”

At the same time, he continues, the “social value” of culture necessarily declines because the recruiting of new members of the intelligentsia extends increasingly to lower social strata, especially that of the petty officialdom. Thus, the notion of the proletarian is formalized; it appears as a mere structure of consciousness, as with the upper bourgeoisie, which condemns anyone not familiar with the rules as a “prole.” The genesis of this process is not considered and as a result is falsified. By calling attention to a “structural” assimilation of consciousness to that of the lowest strata of society, he implicitly shifts the blame to the members of those strata and their alleged emancipation in mass democracy. Yet stultification is caused not by the oppressed but by oppression, and it affects not only the oppressed but, in their essentials, the oppressors as well, a fact to which Mannheim paid little attention. The flooding of intellectual vocations is due to the flooding of economic occupations as such, basically, to technological unemployment. It has nothing to do with Mannheim’s democratization of the elites, and the reserve army of intellectuals is the last to influence them.

Moreover, the sociological law which makes the so-called status of culture dependent on that of those who produce it is a textbook example of a false generalization. One need only recall the music of the eighteenth century, the cultural relevance of which in the Germany of the time stands beyond all doubt. Musicians, except for the maestri, primadonnas and castrati attached to the courts, were held in low esteem; Bach lived as a subordinate church official and the young Hayden as a servant. Musicians attained social status only when their products were no longer suitable for immediate consumption, when the composer set himself against society as his own master — with Beethoven.

Beyond the important comparative interest of an early 20th-century German debate on this question, Adorno raises some important theoretical questions. How do we explain the existence of an intellectual proletariat? For Mannheim, this was supposedly an effect of elites becoming increasingly influenced by proletarian culture; Adorno, on the other hand, argues that it was just one example of a general underemployment caused by mechanization. And what is the cultural significance of underemployed intellectuals? Adorno makes what would seem – to 21st century postmodernist intellectuals – the obvious claim that there is no necessary correlation between the social status of cultural producers and the cultural status of their products. But I’m not entirely convinced by his example of 18th-century German musicians; he seems to reduce social status to institutional role (“a subordinate church official”). It comes to mind that in fact there have been any number of intellectuals whose relatively minor institutional roles didn’t seem to constitute low social standing per se. (Jacques Derrida comes to mind.) Adorno is no doubt right that there is some looseness in the relation between cultural producer and cultural product; but a more adequate theory of the relationship between class structure and intellectual production remains for another day. Or another post.

At any rate, the bottom line is this: the intellectual proletariat or precariat is older than people think. As is the critical discourse that goes with it.

I’m going to read your post again for more detail. But, in the meantime, here are the results of a Google Books Ngram search: http://ngrams.googlelabs.com/graph?content=+intellectual+proletariat&year_start=1800&year_end=2011&corpus=0&smoothing=3. I couldn’t find the source for the blip in the 1830 period. – TL

Hi Tim, thanks very much for this. That is a great graph!

I guess if one were seriously going to pursue a project of this sort — based on graphing various keywords over time — one would have to think about possible other semi-synonyms for “intellectual proletariat” that might be points of comparison. “Unemployed elites,” something of that sort…

Eli

Thankyou for this! I think that notions of ‘intellectual precariat’, ‘intellectual proletariat’ and ‘un(der)employed elite’ are valuable for the historicising that you are doing here, and also as another way of thinking the problem along with ‘casualised academy’ or ‘precarised workforce’ or indeed ‘higher education crisis’ which sometimes seem (to me at least!) less revelatory of the classed nature of the experience of being, say, an out-of-work PhD – including the very low level of labour organising amongst us. It ties in with this discussion, too.

When I worked on Radical America and most of the board members were unemployed or underemployed PhDs, fellow editor Frank Brodhead called it the lumpen intelligentsia.

#8 on Google already! I like your keyword strategy son!

http://www.google.com/search?q=precariate

very interesting. small contribution: it’s a term under debate in France already in the 1890s.

Thanks, everyone, for such supportive comments! If anyone knows about comparable histories in other countries (European? Non-European? Soviet Bloc, maybe?) I would love to have tips there too…

@Ana, I share your skepticism about the usefulness of “crisis” talk, which always seems to me partly performative and theatrical… But can you say more about how you see the relation between precarity (which is at once a social reality and a discursive construct) and crisis discourse? Haven’t thought about that before.

NB: it seems like the more usual spelling is “precariat,” not “precariate,” so I changed it here!

Hi Eli. I guess I was showing my Australian location, where it seems to me at least that the casualisation of the academic labour force (I think it’s something like fifty per cent of university teaching is now done by people on sessional, aka casual, contracts) is considered to be a facet of the ‘crisis’ in higher education, and is linked specifically with the surplus of graduates to available academic postings (as per the links I share above from Melissa Gregg’s work). The term precarity itself is less likely to be used in that discourse of crisis though I think – possibly just due to a regional preference of some kind! Having said that, this piece has had some circulation.

To paraphrase Marx:

Considering, that against this combined power of the elite classes the primary producers or precariat cannot unite and act for itself except by constituting itself into a mass party-movement, distinct from, and opposed to, all old parties and movements, that this constitution of the precariat into a mass party-movement is indispensable in order to ensure the emancipation of its labour power,

That such labour power can be emancipated only when, at minimum, the precariat is in collective possession of all means of societal production, all commons, etc., that there are only two forms under which all means of societal production, all commons, etc. can belong to them or return to community:

1) The individual form which has never existed in a general state and which is increasingly eliminated by industrial progress;

2) The collective form the material and intellectual elements of which are constituted by the very development of capitalist society;

Considering,

That again this collective re-appropriation, or political and economic expropriation of the elite classes, can arise only from the direct action of the primary producers or precariat, organized in a distinct mass party-movement;

Such permanent organization must be pursued by all the means the precariat has at its disposal.

Hi Jacob,

You know, I don’t really think of this blog as a platform for political organizing per se; more like a mediating space where some reflections on politics, particularly academic politics, can take place, and where Anglophones can learn something (perhaps) about life and politics in French universities. I’m not opposed to seeing explicitly political propositions here, and I think that I follow the logic of your proposal, but who is the “we” in this comment thread that might advance a politics? That’s far from clear, and the readers here are clearly a politically (and socially, linguistically, institutionally) heterogeneous group.

So much for meta-reflections on your comment. A couple of more specific questions about your proposal also come to my mind:

1) What does “emancipation” mean? I’m not sure this is something we can take for granted.

2) Can you say more about why collective re-appropriation “can arise ONLY from the direct action of the primary producers, organized in a distinct mass party-movement”? Or why this “must” be pursued? I’m not really a determinist about political strategy; it seems to me that for any given political goal there are generally multiple ways of getting there, and it’s more a matter of weighing different options than of embracing THE one and only method. Which is why activists generally need to deliberate about strategy. The burden of proof is on you, it seems to me, to show that the “mass party-movement” is the only possible way forward. You know what I mean?

take care, Eli

a great article. thank you sir.