October 17, 2017; revised November 12, 2019

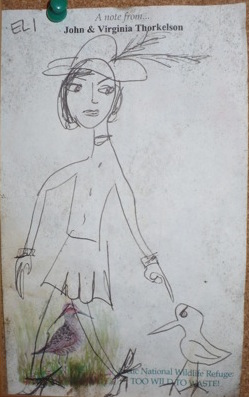

A note from 2019: This is a set of thoughts about nonbinary desire, the longing to escape identity and undo gender, and the rejection of categories. I used to cling to the word “androgyny,” a word I would no longer use so much, but then, as you can see for yourself, it was only ever an anxious placeholder.

1. “I see you as a girl,” said the first girl I was involved with, a long time ago now, it seems like, back when I was a teenager. Sometimes a voice has a curious authority to bring things to life by naming them, and it seems to me as I write that the whole story I want to tell condenses itself into this little remark, I see you as a girl says a girl, a moment where a girl’s eye sees something other than what it’s supposed to see, projects femininity upon what’s supposed to be a boy but really is something more indeterminate. More pliant. In such a moment, gender can become undone, never to be repaired.

2. In my teens girlhood seemed like a livable zone of aspiration, even though now that I’m in my thirties and married, the word girl seems so painfully juvenile. I ought to stay cautious as I write, the better to illustrate my point: that androgyny is something furtive: that caught in the light it hardens and cracks: that it is easily torn: that it easily slips from delighting in its silliness to being a laughingstock. There are those who argue that androgyny is just a natural part of being human, that everyone has masculine and feminine qualities, that gender is continuous or a spectrum; forty years ago Ursula Le Guin introduced her thought experiment The Left Hand of Darkness by saying, “I’m merely observing, in the peculiar, devious, and thought-experimental manner proper to science fiction, that if you look at us at certain odd times of day in certain weathers, we already are” — androgynous, that is, all of us.

But so gentle, so tolerant and so anthropological is this view of things, that it cannot begin to account for the fragility of a skittish androgyny that can only show itself in dreams and shadows. An androgyny that is not explained, moreover, by those who view androgyny as a definite gender identity, like ‘genderqueer’ or ‘nonbinary,’ the two categories with which, if you press me, I identify most closely. Androgyny isn’t an identity; it’s an opposition to identity that’s too systematic to become a movement, too intimate to be a politics, too incoherent to be a category and too uncertain to lie down for examination. I wish I did not even have to name the thing I am trying to describe. Properly, it would be nameless.

3. All the same I want you to see what I mean by it, by androgyny, or if it has no clear meaning then at least I want you to feel some of the tone of its nonsense and its sensations. But this isn’t really an autobiography. It would defeat my point to tell my story as if it were only mine, since my whole point is that undoing gender is a collective affair. Androgyny can’t exist in solitude; it only exists in couples or, better, in communities. Or it surfaces among total strangers in the guise of a menace.

I have memories in sputtering arcs, a series of moments of misrecognition and displacement. Historically, I was often taken or mistaken for a woman by strangers. “Can I help you, ma’am?” asked the airport baggageboy once. “We’re closed, miss,” a guy said as I entered a coffeeshop. “Number 12, ma’am-sir,” a U.S. border guard told me as I waited in line. “Watch out, there’s a lady coming,” a woman said to her young son as I rode past on my bike. “Hola, mija,” shouted some boys in a pickup truck. “Can I have a dollar, ma’am?” inquired a homeless guy outside the bookstore. Then he peered beneath my hat and realized his “mistake,” said, “Oh, sorry, man,” and went on asking me for money. In South Africa, the petrol station attendant greeted me: "Hello, my dear. What can I get you, sir?"

4. The more you have these encounters, the more the conventional signs of gender come to seem frail, the more it becomes obvious that gender is a way of thinking you know someone while not knowing them. The more it happens, the less you know how you feel about it, whether you partly like it, whether it’s flattering. To not be known. Sometimes even people you know don’t know you; once at a grad school party, my classmate didn’t even recognize me when I showed up in a long sweater with immense buttons, eyeliner, and a knit headband. “You’re like a sexually ambiguous Julius Caesar,” she commented after she figured out the face inside the makeup. Later she gave me a hug which I didn’t want, but was too polite to refuse. Androgyny becomes anonymity, conventional affections become afflictions, conventional genders fall and grow to thorns.

5. Androgyny means being repelled and intrigued by gender, gender which gives things their color, like a bruise on the skin, a shadow on the body, a clattering wave. Gender circles you and marks you like prey. When your dad hurries you into his office because he’s afraid his coworkers will see the eyeliner you couldn’t quite scrub away, then you feel gender aloft in the hallways fluttering on wings that no longer carry you. When you cuddle with another body, eyes closed, one person warm against the next and one arm curved around the other, then gender can break and fall off like an outgrown, shedding skin. When in your hallucination you can no longer walk, the world carved up into colors, and you envision yourself as a small mermaid, feet bleeding on imaginary glass shards with each step, then gender rushes up and whispers to you angrily, trying to become human. Your unconscious follows you into your trip.

6. But androgyny isn’t only a romanticized surrealism hiding at the limits of vision; it comes alive in moments of hesitation and uncertainty, becoming the basis for social relationships even as it sets them adrift and askew. I remember one night back in the late 90s: picture the leaves blown black over a hushed sky, trees rustling in the night of the road, footsteps rustling in the night of dingy houses, me and my friend J. walking to the Xtra-Mart at a desolate junction of state highways. J. was tall and dark-haired, secretly needy but outwardly no one to mess with. I was less tall, wore baggy clothes, and had long blond hair in a ponytail, which at the time I thought showed an opposition to authority. We came in through a break in the bushes, crossing the parking lot, and the clerk glanced up at us as we bought candy. J. gave him some money. “So it’s his night to pay?” asked the clerk. The boy is paying for the girl, he was somehow saying. But J. and I shrugged like teenagers and turned our backs. Then we started laughing as we went out through the parking lot.

7. This merry and incredulous laughter turned out to be about the best response I ever got from cis men in the face of genderbending encounters. Meanwhile women, some queer and others not, became my main co-conspirators against gender norms. A lot of the time my partners managed to surprise me, women who sometimes seemed quite straight but turned out to be something else, whose clothes mixed up with mine, whose affective environments I sometimes absorbed, who kept gender firmly at a distance from the norms. Usually they weren’t surprised when I said I was invested in something like transfeminine ambiguity. “I’ve only gotten along with boys who accepted that they were going to be girls quite a bit of the time they were alive,” one person wrote retrospectively. “Males who don’t can be very apt to be violent,” she added. “It makes one very angry to be male all of the time.” The reciprocal fantasy of discarding femininity or aspiring to masculinity can equally be a powerful force among women. Reciprocal fantasies grow in magnitude and duration. Reciprocal fantasies cushion the shock of contact between the scared, the vulnerable and the unlike.

8. Among the remnants of the Chicago hippie counterculture there are (were) spaces where androgyny steals over the margins of the margins, where social norms remain shaky and where gender can therefore become a little experimental, especially if you let yourself be vulnerable to the fantasies of others, if you let yourself be a place where people can project or admire the deviance they don’t necessarily want to enact themselves: spaces where gender is something that gets liberated in groups, where gender gets collectively undone, where gender is the opposite of a choice but also the opposite of a destiny. The collective work of queering gender has a rhythm, expanding at moments, swelling to fill a house, nestling and thistled with scorn and affection.

“You’re not as androgynous as you think you are,” I remember my housemate correctly saying to me once, the one with the long face and the dangerous fainting spells. “On the other hand,” she added, “you’re the most androgynous one in the house.” The next day the next housemate, a physically huge, florid and sharp-tongued man, tells me I seem “totally male” to him. I said I acted especially male around him, that I’m a chameleon, that everyone is a chameleon, that we rhyme with the words people use to describe us and color ourselves the colors we think they see. Later his ex-partner told me that he was really very feminine.

9. So there is never a moment when you can affirm androgyny with much certainty. On the contrary, philosophically speaking, androgyny (for lack of a better word) remains a form of illusion, almost of deliberate self-deception. It involves being indifferent to some of what people think of you, and deliberately ignoring what they ought to think of you, the better to embrace unrealistic, ill-fitting desire. Like ill-fitting but beautifully non-normative clothes. Like for example a desire to be a woman if you’re not one. Or any case, really, where an x is irked by their x-ness and desires instead to be a y or just to be undefined: it involves disavowing not only the usual ways of being but also the usual ways of knowing, believing in the reality of your fantasy and clinging to it in spite of your inevitable ambivalence and fear of embarrassment, taking or trying to take your desires for realities. Which of course is not very straightforward. Especially since androgynous desire is partly a desire for passivity, is partly a desire to let others’ fantasies play across you, partly a desire to be happy about being brought into being by others, a desire to be happy about becoming other. One of the best ways to get a self is to be a thing.

10. So the most believable form of androgyny is the most escapist, is the kind that happens in secret in the eyes of your partner(s), night and dawn passing like squalls. If intense happiness comes as a surprise, it comes in silence. Occasionally you feel beautiful; the bodies cuddle each other and the fantasies cuddle each other. Even though the fantasies tend to tip over and crush the bodies that carry them, and to consume the voice that recounts them. Androgyny has a sexual project that goes along with its aesthetic and psychological projects: it has its ways of wanting and being wanted: it eroticizes your vulnerabilities and anxieties about gender. And it can make the lines between selves get especially blurry, at least for a long moment.

11. Where does this odd story come from, you ask? If I ask myself what kind of history or biography makes it possible for androgyny to rise up through the cracks, I have to think about a world that has unconventional ties and worn norms and a lot of feminine education. I think of my nuclear family, split up by divorce, an extra-powerful mother, a laid-back father, really not identifying with masculinity, getting bullied really horribly for many years by other boys, and being around my mother and sisters but always excluded. I think of being a radically formless teenager, of repetitively buying the most formless possible clothes with no decorations. I think of being happy to escape a state of being totally generic by being invited into a sort of girls’ counterculture, symbolized at the time by Ani Difranco, the feminist icon of the white Northeast. There was rarely anything too traditionally feminine, but there was a lot of egalitarian teaching: here’s how you talk about love, here’s how you wear makeup, here’s a shiny shirt you would like, a pair of pants. A pedagogy of selves and of bodies, here’s how you should kiss me, here’s how I think of what we’re doing together. “We used to be gay together,” a woman wrote to me, I think not entirely jokingly.

12. At times this has all felt more real to me than regular social reality. But it’s hard to affirm it here, first because it’s all so unreal, and second because even the rejection of gender has a political unconscious that makes me queasy. Isn’t it a masculine privilege to disown masculine privilege? Marginal androgyny involves performing a certain status and also, simultaneously, a certain rejection of status. It means giving up some of the privileges of looking like your norm and belonging to your sex group; it involves being constantly misidentified as gay or as straight; but it whispers simultaneously that you are above the norm, that the norm is dumb, that the norm is hideous, that conventional beauty is a nightmare. One part vulnerability and one part smugness, androgyny wants to believe that voluntary exile can also be a form of power. As if being outside and being confused could be a form of superiority and not only of abjection.

But I must still insist that you can’t write off this whole story as just a matter of individual gender privilege and strategy, not even mine. Undoing gender — again this is my single point of certainty — is only ever a collective project. A project that in hindsight I would call feminist.

13. Whose collectivity? Whose feminism? That’s always in question. People always think of coming out as being urgent, and it is, but public androgyny comes at a political price. Who can keep track of all the androgynous rock stars out there? It’s easier to admire it than to live it. Sometimes I think: when androgyny comes out on stage, it loses its power to untie us from within, and, ceasing to be a sly fantasy or an experimental sexuality, it turns into a spectacle, a distant scene where you watch traditional genders getting undermined and then go home to your norms without giving anything up but the cost of your drink. Or worse still, at times, androgyny becomes an advertising image that helps us feel attracted to our things and alienated from the confusions of our longings. Commercial androgynies dampen and soften something that should be nameless, reducing the uncertainties of a look and the comedies of unclassified attraction to stylized formulas.

But you try to forget that.

Instead, you try to cling to the manifesto of your body and to the proving ground of your secrets and to the intimacies you don’t quite know what to do with. For even in an era of nonbinary and trans activism and a certain politics of mainstream inclusiveness, there are things, ways of being, that aren’t included and that maybe don’t want to be included. There are margins on the margins on the margins; there are people who, in spite of the proliferating array of sexual identity garb currently on display, still don’t know who they are, and realize there’s power in not finding out.

14. That’s partly why I don’t usually talk too personally about gender, and why I started writing about this ten years ago without ever figuring out what to do with it. Writing makes things seem like they’re not a work in progress. But I’m so tired of getting worn out by normativity, and nothing feels worse than giving in and going back in the closet, like I used to. Counternorms need to be out and about if they’re going to endure.

So here’s one counternorm, and it’s not only mine.